Local authority pension funds face a challenging future after EU vote

Written By:

|

Jason Lejonvarn |

|

Paul Hatfield |

Deficits on defined benefit schemes have soared to record levels after Britain’s surprise vote to leave the European Union. Mellon Capital’s Jason Lejonvarn and Alcentra’s Paul Hatfield consider what this means for the economy and for pension scheme investments

Britain’s vote to leave to the EU is likely to trigger a degree of stagflation, making life even more difficult for managers of defined benefit schemes struggling to control pension fund deficits, says Jason Lejonvarn, managing director, global investment strategist at Mellon Capital, an investment boutique within BNY Mellon Investment Management. “Over the long term we don’t know how Brexit will play out, but over the short term – the next three to five years – it is certainly not positive,” he says. “Given the policy and the fiscal stance, the likelihood that you are going to see above 2% inflation for at least the short term is pretty high. That will erode the asset side of defined pension balance sheets.”

The Brexit effect

Even before Britain’s vote to leave the EU, rising costs and volatility had made defined benefit (DB) pension deficits a headache for many UK companies. Since the shock result the problem has become even more acute as pension managers’ hopes that interest rates and bonds yields might return to historic norms have been dashed.

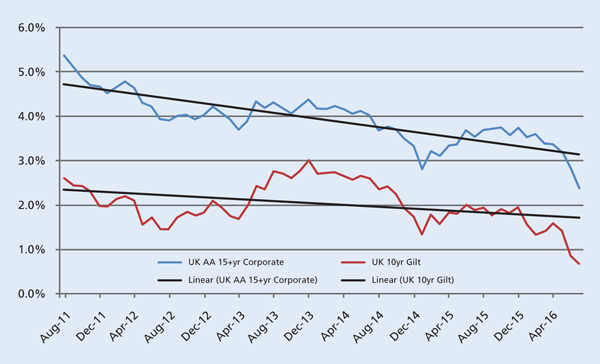

Paul Hatfield, global chief investment officer and president for Alcentra, another BNY Mellon boutique, says: “The expectation was that we were moving into a rising interest rate environment but now it looks like rates will remain lower for even longer.”

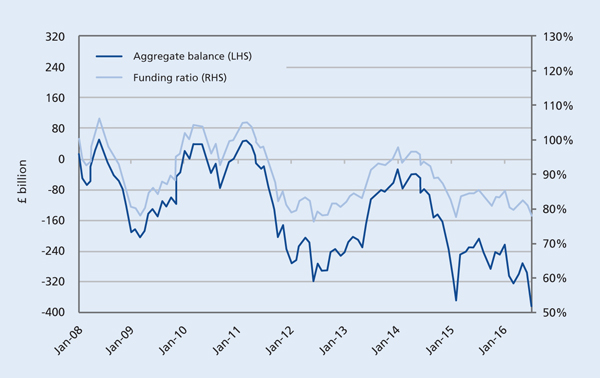

In the days immediately following the referendum, Gilt yields plunged to record lows as investors sought out safe haven assets and markets anticipated further Bank of England easing. According to the Pension Protection Fund (PPF), a 0.1% reduction in Gilt yields raises aggregate DB scheme liabilities by 2% and raises aggregate scheme assets by 0.5%¹.

The sharp fall in bond yields caused the deficit to balloon by £89 billion after the Brexit vote. The total private sector pension shortfall rose to £383.6 billion at the end of June from £294 billion at the end of May, according to the PPF². Some 84% of pension funds are now in deficit.

No relief in sight

The short- to medium-term outlook for pension sponsors and trustees tasked with generating sufficient returns to cover scheme liabilities offers little relief. Although the markets have stabilised since the initial referendum shock, Lejonvarn sees a period of “mini stagflation” impairing returns in the next two to three years.

Figure 1: Historical aggregate balance (assets less s179 liabilities) and funding ratio of schemes in the PPF universe

Source: PPF as at 30 June 2016

If any stagflation materialises it would be a triple blow to pension schemes. Weak UK economic growth means low asset returns. Lower Gilt yields mean the discount rate for liabilities will be lower for longer increasing pension schemes’ liabilities. Above trend inflation would increase indexed liabilities while eroding the real value of schemes’ assets. “I would not say it will be full-fledged stagflation, like in the 1970s, because we are not expecting double-digit inflation and low growth,” says Lejonvarn. “But, what we are looking at is well below trend growth and well above trend inflation in the UK.”

The impact of the rising deficits on wider business and economic life could be significant. Hatfield says: “Businesses are going to have to find ways to fund deficits and that means diverting cash that would otherwise have been used for investment.”

In 2013, when the deficit stood at a smaller £257 billion, the Bank of England surveyed 90 companies with DB schemes. It found that deficits were having a negative effect on investment spending, dividends and pay³. Further cutbacks of investment and wages are therefore likely to harm productivity growth and the UK’s already precarious economy.

It could force more companies out of business and hold up M&A activity. Tata Steel’s controversial plans to water down pension benefits to ease the sale of its British assets and the recent collapse of BHS have already helped to highlight the negative impact of the DB pension crisis on UK businesses – and their employees.

Strategy rethink

Against this difficult backdrop, sponsors and trustees face some difficult choices. Over the past decade, volatile financial markets, low interest rates and rising longevity mean many have de-risked through asset allocation changes. Between 2006 and 2015, the equity share of total assets fell from 61.1% to 33% while the Gilt and fixed interest share rose from 28.3% to 47.7%. The “other investments” share of total assets, which includes hedge funds, property and cash, rose from 10.6% to 19.3%⁴.

De-risked asset allocation models are unlikely to deliver the returns that DB schemes need going forward. Hatfield says: “A portfolio split 50/50 between bonds and shares is probably going to get you no more than 2% over the long term. That isn’t sustainable.”

Altering a scheme’s investment approach is one option for managers and there are a number of ways to do it. To get more yield schemes could take more investment risk, moving from investing in A-rated to B-rated bonds, for example, or shifting more of their global equity component into emerging markets.

Figure 2: UK 10 year Gilts and UK 15+ year AA Corporates Yields: Last 5 years (Aug-11 to Jul-16)

Source: 10 Year Gilts (Bloomberg) and 15+ Year UK Corporates (Barclays) as at 29 July 2016

“Brexit is very domestically driven so you probably want to diversify your assets, such as equity and property, away from a home bias to the extent that you can,” says Lejonvarn. “If your currency risk isn’t hedged you may want to diversify your foreign exchange risk as well.”

With stagflation a possibility, trustees should also be thinking about assets that will provide an inflation hedge, in particular inflation-indexed bonds, Lejonvarn adds.

Taking advantage of low borrowing rates to increase leverage is another option which again adds risk to the portfolio. An alternative way to boost yields is to lock your money up for longer to benefit from a liquidity premium, says Hatfield. “Loans to small- and medium-sized companies may require locking up money for six years but will give you a premium of about 3% on syndicated loans with daily liquidity,” he explains.

However, although pension trustees will no doubt be considering all options, in many cases a scheme’s statement of investment principles will limit room for manoeuvre. For some companies the fallout from the EU vote could therefore be the final straw forcing them to close their schemes. That, after all, is the longer-term trend.

The percentage of schemes open to new members has already fallen from 43% in 2006 to 13% in 2015⁵. In recent years there had been a levelling off of the closure of open DB schemes, though the latest jump in pension deficits could restart the process. Other companies could look to offload their pension schemes to insurers, taking the liability off their books.

Government aid

There is always the possibility that the government will offer some relief. Before she recently resigned as pensions minister, Baroness Altmann had been considering ways to give companies more leeway when calculating their liabilities. In 2012, before she joined the government, Altmann argued for DB funds to use a longer-term average measure of government bonds yields to value their schemes⁶.

“Governments have been pretty tough on defined benefit schemes from a tax and regulation standpoint and should cut them a bit of leeway especially in this low rate environment,” says Lejonvarn.

However, the scale of the deficits means that even if the government heeds calls for more accommodating regulation it is unlikely to offer much relief. For companies running DB schemes times have been tough for many years – the vote to leave the EU has made it that much tougher.

1. Financial Times: Pension deficit grows £89bn in just one month, 12 July 2016

2. Pension Protection Fund: PPF 7800 Index, 30 June 2016

3. Bank of England: Agents’ summary of business conditions, June 2013

4. Pension Protection Fund: The Purple Book, 2015

5. Pension Protection Fund: The Purple Book, 2015

6. Financial Times: Pensions stretched to breaking point after Brexit vote, 17 July 2016

More Related Content...

|

|

|