The case for equally weighting stock positions in a portfolio

Published: June 1, 2021

Written By:

|

Ian Mortimer |

|

Matthew Page |

Ian Mortimer and Matthew Page of Guinness Asset Management summarise what they consider to be the significant advantages of having a concentrated, equally-weighted portfolio

To outperform the market, it is often necessary to do things differently from others – to look at the world through a different lens. One of the ways for a manager to do things differently is at the portfolio construction stage. Rather than size stock positions relative to an index weighting, a manager could instead weight all positions equally across portfolios.

At first glance, the notion of splitting a portfolio into a number of equally-weighted positions may seem a rather rough-hewn approach to take towards portfolio construction. Investors might expect their fund managers to assess consistently the potential upside for every company they own, and adjust their portfolio weightings accordingly. Some may ask that if managers are not changing their weights based on share price movements amongst portfolio holdings, then what are they spending their time doing? Is a portfolio that does not contain larger weightings to the manager’s favourite companies one that lacks conviction?

There are good reasons as to why we believe constructing a portfolio on a concentrated, equally-weighted basis is the best way of maximising the chance of generating good returns while mitigating downside risk. We also believe that this approach demonstrates greater conviction and instils a discipline that ensures that only a manager’s best ideas are deployed.

Why concentrated?

It is first worth considering why managers may run their funds as concentrated portfolios rather than a more broadly diversified portfolio.

Looking at fundamentals, the reason why managers create a portfolio of stocks rather than investing in a single company can be attributed to the benefits of diversification. Each additional stock that is added to a portfolio reduces the potential loss to the portfolio caused by any single investment detracting from overall performance due to a company-specific issue.

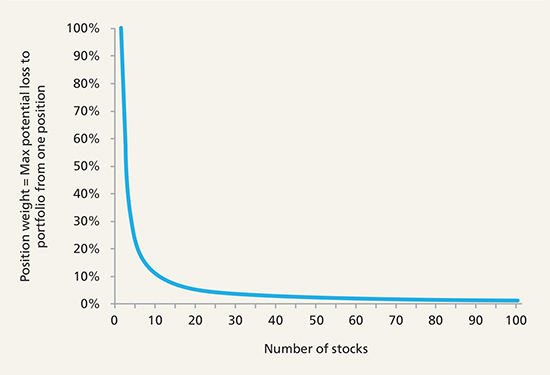

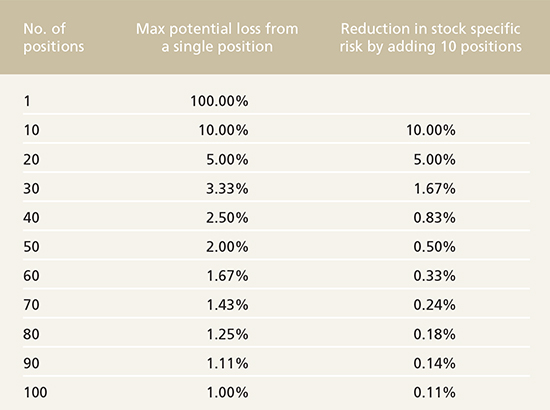

What is interesting is how quickly you can reduce this stock-specific risk to a portfolio by increasing the number of equally-weighted positions within it (as illustrated in Figures 1 and 2). When you have just one position in a portfolio, the potential loss is obviously 100%; with five positions it’s 20%; with ten it’s 10%, and so on.

Figure 1: Maximum potential loss vs number of stocks in a position

Source: Guinness Asset Management

Figure 2: Benefits of stock diversification

Source: Guinness Asset Management

It is important to balance the need for diversification to limit stock-specific risk while still having sufficient weight in one’s positions so that any appreciation will have a meaningful impact on the portfolio. We believe this is achieved by holding between 30 to 35 positions. At 30 positions, one’s maximum potential loss to the portfolio from an individual position is 3.33%, whilst at 35 positions it is 2.86%.

Adding additional positions to a portfolio certainly reduces stock-specific risk, but beyond 35 positions the additional benefit is marginal. At the same time, every additional stock included in a portfolio causes a very linear increase in the amount of time required to perform due diligence and ongoing monitoring.

History shows that unanticipated bankruptcies do take place, and even if one only invests in companies that consistently earn high returns on capital and are very unlikely to go bankrupt, one cannot ignore this risk. Yet if the worst was to happen and a position was to go bust while operating with this approach, in our minds a loss of 2.9-3.3% – though obviously disappointing – would be by no means disastrous to the overall portfolio.

Why equally-weighted?

When you consider the potential total return of a share you have bought, there are really two dimensions to this total return to consider. First is the scale of the total return (both in terms of the size and whether it is positive or negative), and second is the time frame over which the return is realised.

We believe it is possible to identify companies that are undervalued and will likely provide a positive total return. Central to this process is the identification of groups of companies that the wider market underestimates regarding the persistency of their return on capital, before trying to identify the companies within this group that look particularly attractively valued relative to the broader group. Being confident in the likelihood of these types of companies to continue to earn high return on capital in the future means the manager can take a more contrarian view relative to the market, and add companies to the portfolio when they are unloved and offering attractive value.

Regarding a level of confidence in the scale of the potential total return of any individual company, we are very cautious about the usefulness of coming up with a single target price. Instead, it may be preferable to consider a range of valuations. These require some element of forecasting and all methods used are highly sensitive to a number of key assumptions. Given these sensitivities, one’s confidence in any explicit upside must be cautious.

Equally, whilst we think it is possible for a manager to identify companies that are undervalued and will likely provide a decent return, it is difficult to have much certainty in the scale of this return. No manager can find companies that will provide a positive return all of the time, and predicting the timescale over which a return will be realised is a fool’s errand.

An equally-weighted approach takes all the above into account; we believe it is possible to identify companies that are undervalued and will likely provide a decent return, but know it is difficult have much certainty in the scale of this return, impossible to make winning stock picks all the time, and do not know the timescale over which any positive returns may come. By letting every good idea you come up with have an equal weight in the portfolio, the market will decide when a more reasonable valuation will be reached. Running a concentrated, equally-weighted portfolio therefore comes with a number of distinct advantages:

1. High active share

By having a concentrated portfolio with stock weights that are not influenced by a benchmark – as any truly active manager will – then by design one will always have a high active share.

2. Rebalancing effect

Loss aversion is a key behavioural bias that all fund managers need to be aware of and control, but an equally weighted portfolio creates a strict discipline to counteract this. Having an equally-weighted portfolio entails periodic rebalancing – though in order to avoid creating additional trading costs one should avoid rebalancing too frequently (we tend to rebalance every two to three months). This forces a manager to go against the market trend and corresponding media narrative and buy more of the companies that have underperformed the portfolio as a whole and reduce holdings in companies that have outperformed. In a scenario where one of the companies in the portfolio has performed particularly poorly, then the rebalancing process forces a manager to decide whether they wish to continue to own it – in which case they must buy more – or if something about their initial thesis for purchase has changed then they must sell the entire position. What equal weighting enforces is never having a long tail of “legacy” positions in which one lacks real conviction, and only serves as a distraction and potential drag on performance.

3. One-in, one-out policy

Fund managers know that it often seems easier to identify companies they would like to own in a portfolio than it is to find something they already own that they should be selling. Having a concentrated number of positions along with a firmly-enforced one-in, one-out policy forces one to consider which is the position in the portfolio that they like the least, rather than simply adding another position. This keeps a portfolio up-to-date with a manager’s best ideas, encourages ongoing assessment of the companies owned in the portfolio versus the rest of an available universe, and so ensures a high level of conviction is maintained.

4. Limited stock specific risk

Having a concentrated and equally-weighted portfolio limits one’s stock-specific risk to a reasonable level. In a portfolio of between 30 to 35 positions, the fact that no single holding represents more than approximately a three to four percent weight means that one’s stock specific risk is low. If you do not hold an equally-weighted portfolio, then your stock-specific risk is limited to the size of your largest position.

5. Conviction in every position

Some may argue that by equally weighting the portfolio one limits the scale of conviction one can have in any one company. We believe, however, that having much higher weights in five companies and small weights in 30 does not necessarily display higher conviction than having equal weights in all 35.

The equal weighted portfolio construction allows one to have the same weight in a portfolio for a company that has a £1 billion market cap as a company that has a £100 billion market cap. In our minds, this demonstrates high conviction.

More Related Content...

|

|

|