Balancing act

|

Written By: Sinead Colton |

Sinead Colton of Mellon Capital Management explains how Managing portfolio volatility does not need to be done entirely at the expense of growth

It is a conundrum. Ever since the global financial crisis, investors have been keen to flee the damaging effects of volatility; however, that hasn’t abated their thirst – make that need – for growth. Plan sponsors have growing liabilities to meet. Endowments and foundations are facing rising operating costs. And some institutional investors are moving to very specific goal-oriented approaches to address an array of needs.

So how, exactly, do investors mesh these two seemingly diametrically opposed goals of lower volatility and growth-like returns? For now, many investors have gravitated toward absolute-return strategies that advertise zero tolerance for negative return periods. But that comes at a price. In contrast, a better approach might centre on artfully managing long-term volatility (and tail risk) while positioning for growth-like returns.

A history refresher

Before weighing in on this growth versus volatility challenge, step back to consider how we arrived here. The bursting of the housing bubble and subsequent fallout from the great recession of 2008/09 were very painful experiences. The S&P 500® lost approximately 50% of its value during the two-year bear market, and those losses undoubtedly would have been much deeper without the extraordinary intervention by the US Federal Reserve and other central banks worldwide.

Even seven years into a new bull market for equities, the scars from this experience are evidenced by investor attitudes toward growth-oriented assets. Many have responded by de-risking and reducing exposure to equities and other growth assets.

Consequently, this has also resulted in the rise of multi-asset strategies. These approaches offer greater flexibility than traditional approaches, including the ability to short, as well as managing total portfolio risk, rather than active risk. They aim to smooth out the stock market’s bumps in a variety of economic environments. Some of these strategies are absolute return in nature, which means that they typically run at low levels of risk, with standard deviation of roughly 6 or 7%, and they target expected returns in the neighbourhood of cash plus 4%.

“The sales pitches of these absolute-return strategies have been powerful and effective,” explains Sinead Colton, head of investment strategy at Mellon Capital, “particularly since investors have clear memories of 2008. It is no surprise why someone would want to reallocate a portion of their growth capital to absolute-return strategies. But is this really the best approach for all investors?”

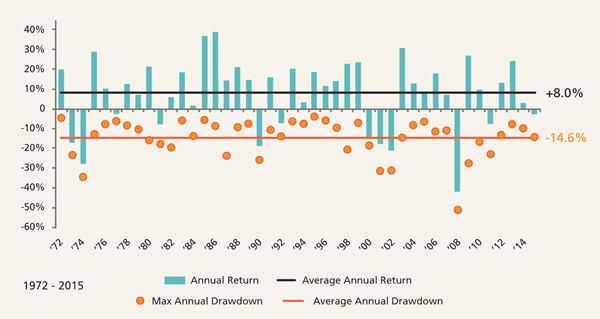

Figure 1: MSCI World (Price) Index calendar year Returns vs. Drawdowns

Source: DataStream and Mellon Capital. For illustrative purposes only. Returns reflect the MSCI World (Price) Index, which measures the price performance of markets represented by the MSCI World Index without including dividends. On any given day, the price return of the index captures the sum of its constituents’ free float weighted market capitalisation returns. Drawdown refers to the largest market drops from a peak to trough during the year, and uses daily returns. Calendar year 1972 is the earliest date daily returns are available for the MSCI World (Price) Index, which illustrate the equity market.

No one is denying the value of a good night’s sleep courtesy of a lower-risk portfolio. It’s true that few endowments and foundations, and especially plan sponsors and their corporate parents, can afford another tail event or the severe drawdown of a market crisis. However, responding to the volatility threat by tilting too heavily toward absolute return strategies could create a returns shortfall.

A better way?

Investors need to reframe this challenge and consider ways to generate growth-like returns in the context of acceptable levels of risk. So rather than focusing on combating the damages of volatility, perhaps endowments and foundations, plan sponsors, and even individual investors facing retirement-funding challenges should be asking: Can I afford to have another decade of growth-oriented assets delivering

4-5%?

“You really need to consider if absolute-return strategies can satisfy long-term requirements, particularly in the context of historical returns for equities of 8% on average [Figure 1], or even compared to more modest future expected returns,” explains Colton, “that’s why we believe that a larger allocation to growth assets merits consideration.”

Consider that over the long term, the average equities drawdown for any calendar year is roughly 14.6% from peak to trough (see Figure 1). That seems much more palatable for most investors given their goals and return requirements. What investors cannot stomach are those periods of severe dislocations – the cathartic experiences with severe drawdowns such as 1989, 1998, 2001 and 2008. The problem is that traditional growth investments do not typically protect significant capital during periods of heightened volatility due to their benchmark-centric approach, and they are particularly exposed to downside tail risk in times of unforeseen events.

Colton, however, believes there is a viable approach that can deliver equity-like returns – slightly less than historical averages – while aiming to restrict drawdowns to within that long-term average of below 15%. In addition to identifying attractive multi-asset investments, this can be accomplished by targeting a volatility range directly, rather than simply accepting the fluctuations inherent to a traditional benchmark centric investment approach.

Focusing on shorter-term volatility measures and then dynamically adjusting exposures to growth assets in response can, in theory, create a smoother return profile over the long-term. This approach offers investors a dynamic asset allocation based on attractive investment opportunities conditioned on the market risk environment – from strongly growth-oriented in robust economic times to more defensive in nature during more tumultuous markets. But this dynamic approach takes resolve, and investors must be willing to re-risk the portfolio and reallocate to growth-like assets at times when volatility is declining. To be effective, this requires timely decision-making and implementation from plan sponsors. The volatility management approach should be symmetrical and disciplined to eliminate any potential missteps caused by emotional decision-making in the heat of a market crisis. Proactive, forward-looking risk management is essential to any investment approach; however, we believe this should be combined with structural and disciplined de-risking that supports risk mitigation strategies as an unanticipated market crisis is unfolding.

“Some naysayers point out that this approach will never allow investors to correctly pick the absolute bottom when re-risking,” admits Colton. “But that’s not what this dynamic approach is all about. It offers a smoother return profile, dynamically managing exposures, with the aim of providing higher targeted returns than typical absolute-return strategies. Minimising drawdowns improves cumulative returns over time relative to traditional assets.” Investors can do this on their own but it’s not easy or without risk. For example, many institutional investors face staffing limitations and resource constraints, not to mention the governance challenges and risk-averse investment committees. And, of course, there are myriad risks associated with behavioural biases.

Opportunity cost

Ultimately, the key for investors is to understand that there are many ways to think about de-risking a portfolio. It doesn’t have to be all or nothing when it comes to growth assets. A managed volatility approach offers some potential advantages, and it can be implemented in conjunction with other strategies, such as liability-matching. “There may be real opportunity costs associated with strategies that target low absolute returns,” Colton reminds us. “If you believe that cash will remain close to zero over the next few years, an absolute return strategy that aims to deliver a return of cash plus 4%, assuming they achieve their target, will deliver a return that hovers around 4% before fees. Is this sufficient for the risk seeking part of your portfolio?

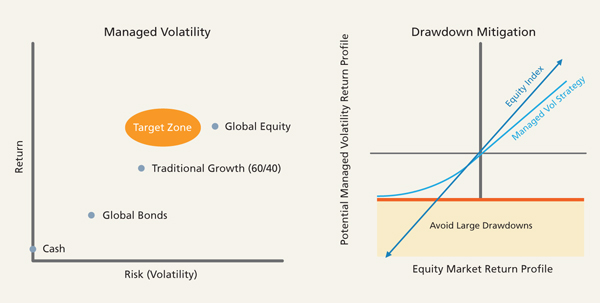

Figure 2: Managed volatility – potentially better risk adjusted outcomes

The charts above are for illustrative purposes only and do not represent actual results.

Source: Mellon Capital, June 2016.

Important information

Past performance is not a guide to future performance. The value of investments can both fall and rise. Investors may not get back the amount invested. Income from investments may vary and is not guaranteed. For Professional Clients only. This is a financial promotion and is not investment advice.

Any views and opinions are those of the investment manager, unless otherwise noted and is not investment advice.

BNY Mellon is the corporate brand of The Bank of New York Mellon Corporation and its subsidiaries.

Issued in the Netherlands and the UK by BNY Mellon Investment Management EMEA Limited, BNY Mellon Centre, 160 Queen Victoria Street, London EC4V 4LA. Registered in England No. 1118580. Authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority.

More Related Content...

|

|

|