Building a stable income stream from a sustainable housing solution

|

Written By: Paul Myles |

Paul Myles of BMO Global Asset Management underlines how an under-supply of housing in the UK is creating opportunities for investors

Housing is high on the political agenda. The population is growing but the housing stock is failing to keep pace with demand, leading to high house prices relative to income. If the economy is to maximise its potential, it needs people with the right skill set, in the right places, and the provision of suitable housing both quantitatively and qualitatively is vital.

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) is predicting that the population will increase by 3.6 million in the 10 years to 2026, while current government policy is to target the building of 300,000 homes a year. In the past, efforts have been directed to the ‘build-to-sell’ market and to increase the level of owner-occupation, but this is changing. A key element of the current housing strategy is to expand the build-to-rent (BTR) market.

The changing pattern of home ownership

Owner-occupation is the goal for many but at current price levels even saving for a deposit is a challenging and prolonged process, so renting is seen as an appropriate alternative, and for a longer period than has historically been the case. Changing working patterns are also affecting the decision to rent rather than to buy; there may be a need for greater mobility in location by employees to match a more flexible labour market. A desire not to tie up capital in one physical asset is also driving rental demand, with renters wanting more disposable income to spend on ‘life assets’ instead – getting married, financing children, holidays. Others may simply prefer to avoid the administration and hassle associated with owning and maintaining a property.

The pace of change has been dramatic with 46% of those aged between 25 and 34 renting privately, compared with 27% 10 years ago. Of the same age group, those buying with a mortgage decreased to 37% (from 57% 10 years ago). The percentage of 35 to 44 year-olds renting privately has risen to 29% from 11% over the same period (ONS).

The private rented sector (PRS) is not new but historically it has tended to be fragmented in terms of ownership, being dominated by small businesses and individuals. Changes to the taxation regime have reduced the attractiveness of buy-to-let and some landlords are withdrawing from the market. This leaves scope for a professional approach to the private rental market focused on providing a longer-term solution for renters, which is affordable, flexible and meets tenants’ needs for space and amenity. With respect to this last point, it is estimated that around 20% of existing private rentals are not fit for purpose, leaving a gap for quality, durable stock, which is reflected in governmental policy to provide a decent standard of living for all, not just above-average earners. The institutionalisation of the rental market could offer the opportunity to standardise the quality of rental stock, fill the gap where private landlords are declining, and provide a sustainable solution from investors seeking longer-term, stable income streams.

The policy response

The government has become increasingly vocal regarding rental accommodation. The situation is fluid but the policy emphasis is clear. The government agency, Homes England, has been radically expanded and empowered, and two funding schemes have been introduced, a Home Building Fund with £3 billion for housing and supporting infrastructure, and a £3.5 billion PRS debt funding scheme.

In July 2018, the government announced proposals to introduce compulsory three-year leases but with a break clause for tenants – the average rental occupancy period is four years. The National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF), published in July 2018 following consultations, raised the profile of affordable housing and BTR with local authorities as an alternative to home ownership. It states that affordable housing is to be sited in large schemes, with BTR being one strand of provision. Local plans are in various stages of development. Affordable housing is being seen as a priority; in London, the Mayor plans to build at least 116,000 affordable homes by 2022.

There is scope for partnerships involving local authorities and housing associations to join forces with institutions to deliver housing provision outside of the top decile high-end homes, which tends to be the focus of the ‘buy-to-sell’ market.

The residential investment market

The UK residential property market is significantly larger than the UK commercial property market, buoyed by the owner-occupied market. Additionally, the private rented sector is bigger than the commercial property investment market. However, mainstream investors have focused on commercial rather than residential property.

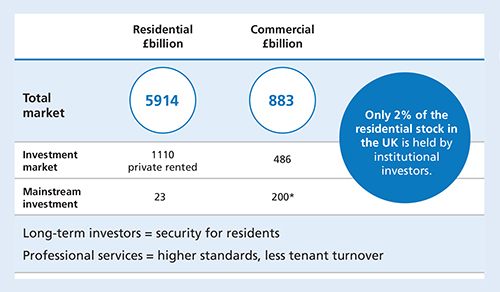

In Figure 1, data from the Investment Property Forum (IPF) summarises the position. In 2016, the UK residential market (excluding student accommodation) attracted only £23 billion of mainstream investing. It is, however, becoming an increasingly popular option with institutional investors. Data from IPD shows the share of the Annual Universe attributed to residential, rising to 7.4% in 2017 from 3.5% in 2010.

Figure 1: Size of residential and commercial property markets

*IPD Annual Universe 2017 ex residential

Source: IPF Size and Structure of the Property Market July 2017, IPD Annual Digest 2017

The LGPS Investment Regulations of 2016 may also increase the attractiveness of residential investment for pension funds. The regulations focus on infrastructure, and this has been identified by the pools as an area where they wish to increase their strategic allocation. Private rented housing falls within this definition.

There is a weight of money looking to invest in residential, private rented and BTR stock. Data from CBRE (June 2018) has identified £32.7 billion of institutional finance seeking to invest in the PRS sector in the UK over the next five years, both from the UK and overseas, under-scoring the appeal of the sector.

Build-to-rent in practice

BTR is defined as multi-unit blocks of private rented housing in single ownership. It is newly constructed, purpose-built, operated as a single investment and professionally managed. The NPPF states that leases should typically be for three or more years. BTR goes beyond the physical type of stock to involve an operational model.

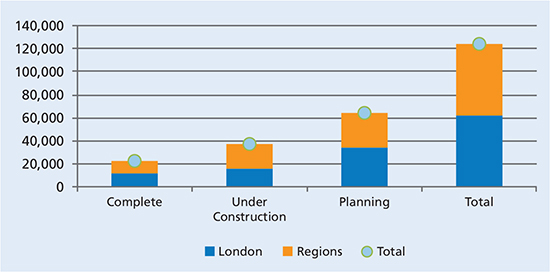

BTR is a relatively new concept and a small sub-set of the wider residential market. Data from the British Property Federation (BPF) and Savills in Figure 2 shows that it is growing rapidly. The total pipeline of more than 120,000 in June 2018 compares with around 35,000 in early 2017. Initially, schemes were focused on London, especially East London, but more recently activity has broadened. The schemes in the pipeline are also becoming larger in terms of the number of units provided in each development.

Figure 2: Build to rent completions and pipeline, June 2018 – number or units

Source: British Property Federation, Savills, June 2018

The current rate of activity falls a long way short of demand; the volume of building will not even fulfil the one-year delivery quota. However, there are positives on the horizon. The BPF estimates that 44 BTR schemes are currently under construction, of which 21 are believed to be institutionally-backed. There are 71 BTR schemes in the planning pipeline. An analysis by the BPF indicates that if the BTR were to mature at the pace of the US multi-family market or UK student purpose-built accommodation, it could be delivering 15,000 homes per year by 2030. By then, the BPF argues, the market size would be £60 billion.

This is an area where access to specialist skills and intensive due diligence on the particular scheme is critical. The past few years have seen numerous tie-ups between fund managers and housebuilders and developers, particularly through forward-funding and forward purchase, which can be more tax efficient.

The attraction of BTR to the institutional investor

The position is changing radically for professional investors. In addition to the structural changes noted in the previous section, investors are being attracted to residential for a number of other reasons, including:

- Potential for high and relatively stable total returns

- Defensive characteristics

- Certainty of cash flow

- Lower voids

- Ability to add value

- Economies of scale

- Inflation linkage

- Diversification

- Environmental, social and governance (ESG) benefits

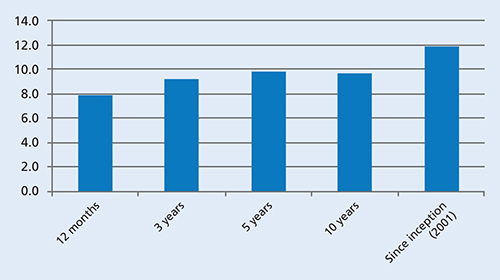

Figure 3, below, illustrates the past performance of residential property. Since the Quarterly Index was introduced in 2001, residential investment property has delivered an average total return of 11.8% per annum versus 7.8% per annum for all-property, and was the strongest performing component in IPD’s global property classification scheme. Residential property total returns have also been less volatile than all-property and equities over time. Past performance, however, should not be seen as an indication of future performance.

Figure 3: Residential total returns to June 2018, % per annum

Source: IPD Quarterly Digest June 2018

Residential investment property, as measured by the IPD, was also notable for its relative resilience during the global financial crisis, with a shorter and shallower dip. Additionally, performance remained positive during the dislocation caused by the referendum result in June 2016. In capital value terms, residential property investment has seen a rise of almost 80% in capital values versus less than 10% for all-property in the ten years since June 2008.

The key element of the investment return is income. The residential sector benefits from an annual income return of 3.8% in the year to June 2018 and 3.5% per annum over 10 years. This has provided a consistent support to performance. The quarterly income return has never been negative and has never fallen below 0.6% per quarter since the Quarterly Index was introduced. This certainty of cash flow is likely to be attractive for investors seeking a secure income stream. This is especially true in the current low interest rate environment and given the Bank of England’s comments, related to its new (r-star) measure, which is the interest rate when monetary policy is neutral. The Bank believes that the rate is lower than in the past. If interest rates do normalise at a lower level than in the past, an annual income return above 3% starts to look even more attractive.

BTR also offers the opportunity to raise rents over time and by doing so could provide a measure of protection against inflation. The dynamics of demand and supply for residential property have also kept void rates low. Latest data shows the vacancy rate equating to 4% of income which is well below the all-property average of 7%.

It is early days, but there is scope for a relatively large-scale professionally-managed operation to add value through active management and the harnessing of economies of scale. For the investor, BTR can offer advantages over other forms of residential investment by enabling access to larger lot sizes, which have this ability to enhance value.

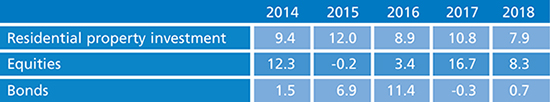

The residential property market is driven by different factors than commercial property and other asset classes. As a result, it can potentially provide diversification benefits. The asset class has also performed credibly against equities and bonds over the past five years. Property investments can, however, be illiquid and their value and any income from them can go down as well as up and investors may not get back the original amount invested.

Figure 4: Total returns – year ended June %

Source: IPD Quarterly Digest June 2018, MSCI June 2018

ESG benefits

Investment in residential property can deliver benefits from an ESG standpoint. Each scheme is different, but key aims would be to increase the supply of homes that are affordable in the local market context, provide homes built with longevity in mind in terms of environmental efficiency and durability, and provide homes that are compatible with enhancing the community. The landlord is one entity with full oversight of an entire complex and it is in the interest of the long-term invested landlord to maintain desirability of the development as a whole.

Attuned lines of communication between the residents, property management and the landlord allow for a governance structure that can flawlessly feed back residents’ views and ambitions for their community to those who can enable change. Traditional restrictions, such as with parking spaces and permitting pets, can be removed, and opportunities, such as group discounts for services, can be realised. Furthermore, data from a BTR community can be more seamlessly obtained for monitoring such environmental indicators as energy usage, not usually attainable in private rented properties.

A solution best served by institutional investors

As well as a real need for longer-term, affordable rental properties there is also a desire from the current government for the solution to be sustainable, and this is unlikely to change with successive governments. The appropriate solution needs a consolidation of higher quality assets and higher standards of maintenance and service. This requires a level of expertise and governance that lends itself to institutional investors.

© 2018 BMO Global Asset Management. All rights reserved. BMO Global Asset Management is a trading name of BMO Asset Management Limited, which is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. CM15278 (11/18) UK.

More Related Content...

|

|

|