Climate change and real estate

|

Written By: Sophie Carruth |

Sophie Carruth of LaSalle Investment Management looks at how the real estate sector is facing up to the challenges presented by changes in climate patterns

There is more than just growing interest in responsible investment and climate change among the Local Government Pension Schemes. Increasingly, the pools and their constituent funds are committing to fully integrating these themes into their investment policies. This includes aligning investment portfolios with the goals of the Paris Agreement, targeting low-carbon benchmarks and reducing exposure to carbon-intensive assets. To date, four of the pools have signed up to the United Nations Principles of Responsible Investment.

At LaSalle, we believe that integrating the impact and risks posed by climate change into both investment decisions and the ongoing management of assets is fundamental to successful long-term performance. Property will continue to deliver attractive risk adjusted returns provided that climate change is embedded in selecting and managing the right assets.

The UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Report published in October this year was a timely reminder of the urgency with which climate change must be tackled to prevent catastrophic impacts on our planet. It states that serious action must be taken in the next 12 years in order to limit global warming to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, because anything higher will have dangerous consequences for our planet. In the report, buildings and cities are highlighted as key areas that need to make drastic changes to reach this target. Real estate, therefore, is in the spotlight when it comes to the seismic shift that needs to occur in the relatively near future.

As well as being a major contributor to the problem, real estate is also hugely affected by the physical changes that are already starting to occur as a result of global warming. These include rising sea levels and extreme weather events, as well as higher average temperatures. Early obsolescence is a major issue given that most existing buildings are simply not designed to withstand these extremes. Higher winds will affect cladding, higher temperatures will overload cooling systems, and poorly insulated buildings will suffer from overheating. Many historic buildings with gutters designed a century ago are already struggling with current levels of rainfall. Many buildings will require significant capital expenditure to bring them up to a standard that is appropriate for the new normal, whatever that is. In the worst cases, buildings will simply no longer be fit for purpose and will need to be demolished.

Beyond the physical risks of climate change, other risks must be taken into consideration. Countries that have committed to the Paris climate change agreement will push responsibility down to energy consumers, which will present regulatory risk. The inability to insure buildings in areas of high flood risk is already a reality, but when areas flood repeatedly, what then for the buildings in those locations? Mitigation measures must be factored into the design of new buildings, but ideally we wouldn’t build in areas of high flood risk at all, a questionable prospect on this island in the midst of a housing crisis. There will also be secondary risks, such as the massive increase in migration by those affected by climate change.

Despite this, it’s not all doom and gloom for property. The good news is that climate change also presents some opportunities for investors. The generation of on-site renewable energy can offer a particularly attractive triple benefit: photovoltaic arrays (solar panels) can offer tenants cleaner and cheaper energy, as well as attractive returns to the investor.

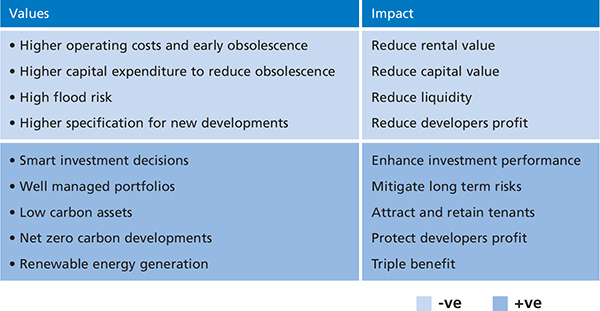

Figure 1: Ways in which change can impact on values

Source: LaSalle Investment Management

Climate resilience requires both mitigating further climate change (i.e. reducing greenhouse gas emissions) as well as adapting to the effects of climate change (i.e. mitigating the risks outlined above). Buildings need to emit less carbon and be able to withstand climate change. Such climate resilient buildings will eventually become the norm, especially as tenants increasingly demand these characteristics in their occupied space. As investment managers, our job has always been to build portfolios of assets that continue to attract tenants in order to safeguard cashflows. Climate change simply adds another dimension to this.

Investors need to be sure that their real estate managers have embedded the risks and opportunities into their decision-making processes in order to protect and enhance returns. We believe it is important that issues presented by sustainability are reviewed at each stage of the asset life cycle, from investment strategy, acquisition, development, leasing and throughout the hold period. Engagement with key stakeholders such as property managers is key to ensuring that ambitions such as energy and greenhouse gas reduction targets are clearly understood by all in the supply chain. Ultimately, the space occupied by tenants falls within the sphere of influence of an investor, and although it can be challenging, engagement with tenants where possible can help ensure that they drive down the environmental impact of their occupied space.

The wider real estate industry has rallied to tackle the challenge of climate mitigation, with a number of initiatives aimed at reducing carbon emissions of buildings. The World Green Building Council launched the Advancing Net Zero project in 2016, defining a net zero building as one that is highly energy efficient with what little energy it does use being renewable and generated on-site and/or off-site. The project’s key milestone dates are for all new buildings to operate at net zero carbon by 2030, and for 100% of buildings to operate at net zero carbon by 2050. These are intentionally long-term milestones given that the changes needed to achieve them will take time. This long-term view aligns neatly with long term investors like pension funds, but is still off-putting to shorter term actors in the industry such as developers, who may face legislative penalties for not acting more quickly.

On the resilience side, the Committee on Climate Change this summer made recommendations to the UK government to strengthen new-build standards to ensure they are designed for a changing climate, are future-proofed for low-carbon heating and deliver high levels of energy efficiency. The government consultation and subsequent implementation will take time, and will only apply to a tiny minority of our total building stock, but it is progress in the right direction.

Climate change is clearly a global challenge and it will require a co-ordinated global effort to deal with it. The Taskforce for Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), driven by the Financial Stability Board, published its recommendation report in 2017 which outlined a framework for transparency. The core elements of the report being: Governance, Strategy, Risk Management and Metrics & Targets. The framework applies to all asset classes, all of which are currently grappling with practical solutions for reporting in line with the recommendations. This means establishing a methodology for calculating the value at risk, based on various climate change scenarios (eg a 2°C increase). LaSalle is actively participating in the UN Environment Programme Finance Initiative real estate pilot to tackle this challenge, the results of which will be publicly available in early 2019. When published, the methodology will encourage managers of and investors in real estate to introduce a new level of transparency to the financial risks brought about by climate change. It will also highlight some of the opportunities available to investors in property, such as increased returns through generating renewable energy.

Conclusions

Whilst managers of real estate portfolios are responsible for making these changes happen, investors, whether investing directly or indirectly in real estate, can certainly help accelerate the changes by incorporating climate change into investment principles and challenging managers to drive transparency around climate-related risks.

For the LGPS, investing in real estate is intended to deliver long term returns so that scheme members can enjoy their retirements, but if those very investments contribute to a world that will not be habitable, there seems to be a fundamental conflict. In order to bring resilience to these investments, we need to bring climate resilience to the underlying buildings. It is clear to us that real estate will continue to have a role to play for scheme members, both in providing attractive and sustainable cashflows to pension funds, and ensuring that those returns don’t come at the expense of the environment into which pensioners will retire.

More Related Content...

|

|

|