Commercial mortgages looking cheap again

|

Written By: John Barakat |

John Barakat of M&G Investments discusses the significant advantages offered to pension schemes by senior real estate debt

Commercial mortgage lending has attracted significant interest from pension schemes over the past 10 years, drawn by its diversification benefits, defensive characteristics and stable cashflows secured against physical assets. Today, senior real estate debt offers some of the most significant value relative to corporate bonds of similar ratings seen since 2011. Nonetheless, real estate debt is an illiquid investment class best suited to long-term investors happy to accept an element of short-term illiquidity as well as capital at risk.

For pension scheme portfolios, an allocation to senior real estate debt (mortgage loans secured against a physical piece of real estate with a first priority call) has typically offered attractive outcomes as follows. First, the opportunity for greater return than bonds of similar credit quality – albeit in exchange for giving up some liquidity and for gaining exposure to risk of a loss in value of the real estate. Second, it can generate stable, regular cashflows for institutional investors thanks to its fixed income properties.

Third, the lender can benefit from investor protection in the form of financial covenants negotiated deal-by-deal, which can act as early warning signs of any deterioration in the performance of the underlying property. Fourth, it offers the investor security against a physical asset, which typically allows for higher recoveries than for unsecured corporate debt in the event of a default.

Offsetting this, investors bear liquidity risk, since commercial real estate loans are often bespoke and so are held until maturity; and the risk that a borrower may default and fail to repay the loan. Finally, real estate debt incorporates the risk that a downturn in the property market may negatively affect the value of the underlying property – and so increase the risk of the mortgage loan not being repaid.

A shift in the lending landscape created an opportunity

In the years that preceded the global financial crisis, Europe’s real estate debt landscape looked very different to how it does today. Most commercial mortgage lending was provided to borrowers by banks. Lending criteria were less stringent, with typically high “loan-to-value ratios”, a measure of the size of the loan in comparison to the value of the property. Property valuations had reached a peak, and returns on lending were low.

The financial crisis kick-started a broad wave of de-risking in the banking sector and sparked the introduction of more stringent capital requirements for banks through new regulations such as Basel III. This led the banks to scale back their dominant position as providers of real estate lending.

Yet demand for real estate debt finance only continued to grow, with alternative, non-bank lenders – such as institutional asset managers investing on behalf of pension schemes – moving into the former territory of the banks. It is a growth trend that shows no signs of abating, with non-bank capital now representing 7% of the European commercial real estate debt market, compared to just 1% in 2008.

Relative value in senior loans is now highly compelling

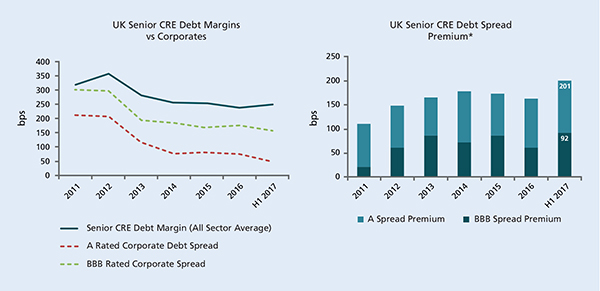

Senior real estate debt offers a particularly attractive investment opportunity at the present time. Over the past two to three years, credit “spreads”, the return over and above government interest rates that an investor gains for accepting the risk of a corporate bond, have been generally trending downward, while in the real estate lending market, both the spreads offered and loan-to-value levels have remained relatively stable, offering an attractive relative return. Corporate bond spreads have narrowed as investors have worked to combat the effects of monetary policy in the UK by buying into higher yielding assets.

At the same time, real estate borrowers have become more conservative following the financial crisis, keeping senior loans to a relatively conservative proportion of the property’s value, while a more stringent regulatory environment has led to a reduction in lending provided by banks.

The outcome has been to make the relative value offered by real estate debt in comparison more evident and more compelling than it has been since 2011.

Whilst investors expect to be paid an illiquidity premium, the relatively short terms of commercial mortgage loans, of three to five years in length, coupled with income from quarterly interest coupons, ensures that investors are being more than fairly compensated for the perceived illiquidity of the asset class.

Figure 1: Attractive risk-adjusted returns through the cycle

Source: DeMontfort Mid-Year 2017 Commercial Property Lending Report (CRE Debt margins), Bank of America Merrill Lynch (BBB and A rated GBP corporate 3-5 year asset swap spread). *UK Senior CRE Debt Spread Premium calculated as the difference between the equally weighted average of CRE debt margins from the De Montfort University report and the BofA Merrill Lynch 3-5 year BBB and A rated GBP corporate asset swap spreads.

However, in order to release the relative value, the key for pension schemes is their ability to access these investments. Real estate debt is a complicated asset class which requires skilled and thorough underwriting of both the loan itself and the underlying property, in order to negotiate the best possible terms for investors with tailored loan covenants. We believe that asset managers with the expertise and resources to lend whole loans directly to borrowers are best placed to do exactly that.

Refinancing represents a robust source of demand

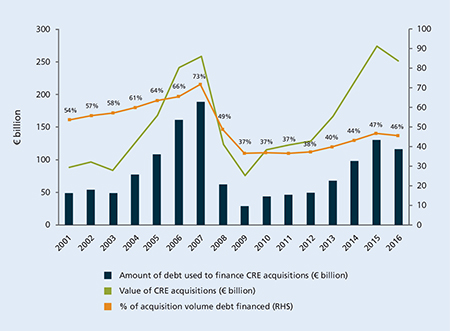

Real estate lending represents a growing market, as the volume of deals has risen, which in turn means that the absolute value of debt required has increased. As Figure 2 below shows, the proportion of commercial property acquisitions financed by debt has grown steadily since the global financial crisis, with CBRE estimating that 46% of a record €255 billion of European commercial property investment in 2016 was financed by debt.

Figure 2: European real estate acquisitions and proportion funded by debt

Source: Amended from Figure 2 of CBRE “European Commercial Real Estate Finance 2017 Update”

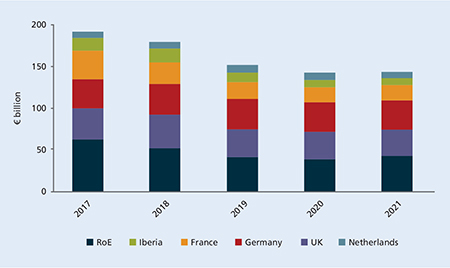

It’s not just new acquisition financing that is drawing in lenders. The refinancing of existing mortgage loans is also a large part of the market, creating a pipeline of investment opportunities over the medium term, as shown in Figure 3 below. In the next three years, around €500 billion of real estate debt in Europe is expected to reach maturity, and therefore need refinancing.

Figure 3: Maturity profile of European real estate loans (€ billion)

Source: Amended from Figure 4 of CBRE “European Commercial Real Estate Finance 2017 Update”

Hard work pays off in a whole loan approach

Typically, investment managers opt either to buy loans from banks once the terms have been negotiated and agreed, or to take a direct origination approach by structuring and signing loans with borrowers directly.

Direct origination takes more time and resources than simply buying a position in a loan, but it comes with three advantages: it enables the lender – the asset manager on behalf of clients – to establish a direct relationship with the borrower; it gives the manager control over the loan structuring and transaction documentation and thus the ability to secure tailored covenants; and it empowers the manager to set the price of a loan directly with the borrower, instead of accepting a return set by the syndicating bank and paying a fee for that service. The manager’s clients further benefit from keeping any origination fees rather than passing them to an originating bank.

Loan-to-value metrics for senior real estate loans have stabilised at lower levels since the crisis, with ratios typically in the range of 55-65% of a property’s value in the UK and Europe.¹ As a result, senior loans offer insulation against a fall in the value of the underlying real estate, and can typically withstand a drop of 35-45% in the property price before the senior lender would incur a loss.

At higher loan-to-value levels, borrowers typically need to secure junior or mezzanine financing to fill the gap between senior debt and equity. This can be provided either by a specialist mezzanine lender, or a lender that can provide “whole” loans, encompassing both junior and senior tranches, which can be split into senior and junior tranches after the investment is made.

The ability to write a whole loan can make better financial sense: borrowers are typically willing to pay more for this one-stop solution rather than having to negotiate terms with multiple parties, while the expanded pool of borrowers opens up access to a wider range of deals and enables managers to be more selective.

By splitting a whole loan into senior and junior tranches – each with different risk and return profiles – managers can allocate risk to investors as efficiently as possible. The tranches are usually sized to investment-grade and sub-investment-grade ratings, respectively. However, investing in both senior and junior tranches requires careful management to keep the interests of both sets of investors aligned in the event of a loan default or significant deterioration in the value of the underlying real estate.

For pension schemes, which are by their nature long-term investors able to accept some illiquidity in the short term, senior real estate debt now offers an attractive investment opportunity.

For Investment Professionals only. Not for onward distribution.

This article reflects M&G’s present opinions of current market conditions. They are subject to change without notice and involve a number of assumptions which may not prove valid. Past performance is not a guide to future performance. The distribution of this article does not constitute an offer or solicitation and should not be considered as investment advice or as a recommendation of any particular security, strategy or investment product. Information given in this article has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable although M&G does not accept liability for the accuracy of the contents.

M&G Investments is a business name of M&G Investment Management Limited and is used by other companies within the Prudential Group. M&G Investment Management Limited is registered in England and Wales under number 936683 with its registered office at Laurence Pountney Hill, London EC4R 0HH. M&G Investment Management Limited is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority.

1. De Montfort Year-End 2016 Commercial Property Lending Report.

More Related Content...

|

|

|