Disruption and the new world order

Published: October 1, 2018

Written By:

|

Regina Chi |

Regina Chi of AGF Investments examines the current shift in the global supply chain, China in particular, and investigates how investors could profit from this change

From Artificial Intelligence (AI), self-driving cars, fintechs and drones, China is gaining a reputation as the world’s innovation capital. In fact, the phrase “made in China”, once emblematic of low-end trinkets and cheap labour, is getting a makeover as the economy undergoes a seismic shift.

This transformation – arising against the global backdrop of growing populism, trade protectionism and sweeping technological change – is having a dramatic impact on the world’s supply chain, the network of companies that provide everything from the bits and pieces needed to make our electronics run, to the leather and other materials that go into our footwear and apparel. These suppliers not only serve as a barometer for the future outlook of an Apple stock, for example, but provide rich investment opportunities themselves. In other words, shrewd investors may do well to heed this advice: follow the supply chain.

Birth of the supply chain

While globalisation has been underway since the birth of the telegraph and the Pacific railroad, it’s hard to believe that the notion that developed countries would work with supplier companies in emerging economies to cut costs is only a few decades old. This trend truly gained momentum following the North American Free Trade Agreement when US car manufacturers outsourced much of their labour to Mexico. Meanwhile, the next iteration of global outsourcing evolved with the increasing sophistication of technology. With multinationals focused on their sweet spot – product design and brand – they’ve turned to suppliers to make their components. They’ve looked to China and other parts of Asia as sources of cheap labour, land, and for economies of scale, to feed a seemingly insatiable demand for consumer goods.

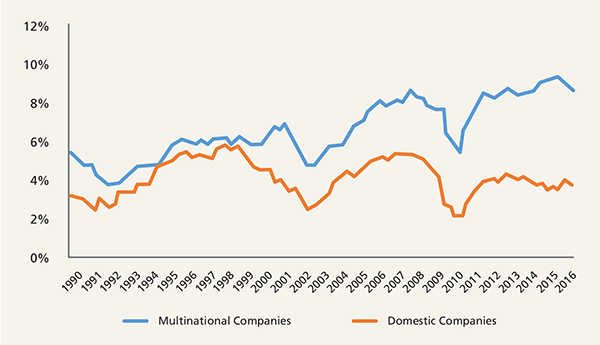

For more than two decades, there have been clear winners in this wave of globalisation. While multinationals have outperformed their domestically-focused rivals, emerging market economies have also flourished, benefiting from the surge of foreign investment, while contributing to a bigger share of the world’s GDP, according to World Economics and data from Barclays Investment Bank Research (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Net Margin, Multinational vs. Domestic Companies

Source: World Economics, Barclays Investment Bank Research

Disruption and the new world order

However, we believe we’ve reached a tipping point. A new world order is emerging, reshaping the global economy, driven by a wave of forces that are threatening well-trod trading patterns and the integration of economies. The risk? The winners of these last two decades could well now become the losers – and they are especially high for emerging markets – particularly those in the Asian value chain.

Tit-for-tat trade wars and the advent of economic nationalism are helping to drive deglobalisation. But the acceleration of technological innovation, including Artificial Intelligence (AI), automation, robotics and 3D printing is also having a dramatic impact on both the emerging and developed markets, especially as they displace traditional production capacity.

This will, in all likelihood, impact the flow of investment to emerging markets, with automation eliminating 40-60% of jobs in emerging markets, according to the World Bank’s 2017 estimates. And those multinationals who are quick to embrace emerging technologies may benefit from on-shoring, thereby avoiding the onslaught of disruption wrought by deglobalisation.

Take Adidas, the global athletic brand giant. The company has built an advanced automated facility in Germany using 3D printing that promises to develop, manufacture and restock footwear in a matter of days, as opposed to orders from China taking many months, produced with a fraction of the standard workforce.

By improving efficiencies, local production also has the potential to strengthen company balance sheets with reduced inventory costs, lower capital spending, shortened transition lag and overall improved return on invested capital. The downside is that easy access to technology such as 3D printing also lowers barriers to entry, potentially increasing competition for reigning brands too.

The rise of “Chinnovation”

While all of these forces are conspiring to challenge the status quo, events within China’s borders are also helping to accelerate these shifts in the global supply chain. The recent explosion of China’s technological firepower, coupled with new state-driven policy, will create a domino effect in local emerging markets.

The country is undergoing an astonishing transformation – from serving as an imitator and the world’s factory floor for cheap goods to a country vying to realign the power of the global technology industry in the coming years. Some have dubbed this shift to a designed-in-China model as “Chinnovation”. For now, the old smokestack industries and new start-up worlds co-exist, but structural changes are occurring at a breathtaking pace.

China’s ambitious Made in China 2025 policy, a strategic plan issued by the government in 2015, is helping to drive its economy, focusing on high-tech industries that have typically the purview of foreign companies. The country is driving technological innovation in emerging areas like robotics, AI, Big Data, as well as genomics, clean energy, electric cars and aviation. The Made in China plan also outlines a strategy to boost Chinese-domestic content of core materials 40% by 2020, and 70% by 2025. To achieve its goals, China has also made impressive investments in research and development (R&D), and patents. China has been granted the largest number of patents globally since 2015, growing 22% compared with just 7% in the US, according to data gathered by IP5 Offices and UBS Group AG.

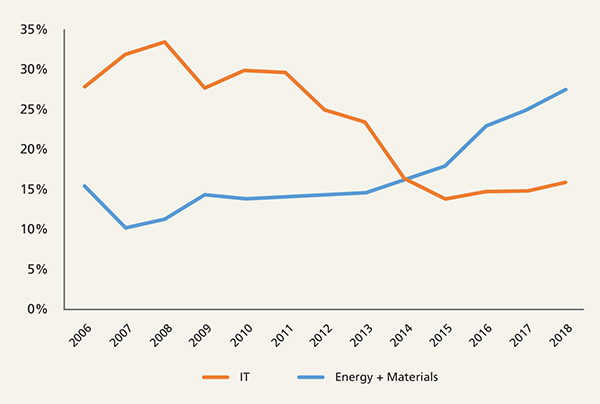

These developments are already having a significant impact across the surrounding region. Consider that information technology (IT) now has a bigger weighting on the MSCI Emerging Markets Index, far outpacing its traditional stronghold in energy and materials, according to data from Thomson Reuters Datastream and HSBC (Figure 2).

Figure 2: IT and Energy+Materials weighting, MSCI Emerging Markets Index 2006-2018

Source: MSCI, Thomson Reuters Datastream, HSBC, August 2018.

However, shifts in the supply chain won’t happen overnight. This will take two to three years to unfold if current dynamics hold. But as China steps up the value chain, countries such as Malaysia, Bangladesh, Vietnam and Taiwan will also transform. For example, we know Vietnam is already attracting a rush of new investment, with textile makers and semiconductor companies setting up shop. Meanwhile, India is also playing a bigger role, trumpeting its engineering know-how.

However, if scale loses its importance in a less integrated world, there are also worries about the long-term sustainability of lower-value countries like Taiwan, Bangladesh and Thailand.

What does this mean for investors?

From an investment perspective, this disruption in the global value chain has far-reaching implications. As we’ve said, there will be clear winners and losers. Those who stand to benefit most include companies with strong intellectual property and patents whose goods and services cannot be turned into commodities. Meanwhile, multinationals with strong brands stand to gain, too.

Other winners could include commodities and agriculture – after all, items like wheat and copper can only be produced in specific geographies and cannot be displaced by technology.

What do we look for? Beyond companies that make good capital allocation decisions including high R&D spend, and that continue to invest in intellectual property, we look for companies with strong balance sheets that help enable investment in new technologies, especially in a downturn. We also look for companies that earn a rate of return above the cost of capital – critical in an era of rising interest rates.

In other words, investors would do well to position themselves for these tectonic shifts, heeding the advice of this ancient Chinese proverb: “A fly before his own eye is bigger than an elephant in the next field.” In other words, you can’t find tomorrow’s opportunities by focusing on today. Investors should keep their sightlines squarely focused on China’s shifting role in the global supply chain, the acceleration of technological innovation, and the impact deglobalisation will likely have on both developed and emerging markets in the future.

References to specific securities are presented to illustrate the application of our investment philosophy only and are not to be considered recommendations by AGF Investments. Every effort has been made to ensure accuracy in these commentaries at the time of publication; however, accuracy cannot be guaranteed. Market conditions may change and the manager accepts no responsibility for individual investment decisions arising from the use of or reliance on the information contained herein. Investors are expected to obtain professional investment advice.

AGF Investments is a group of wholly owned subsidiaries of AGF Management Limited, a Canadian reporting issuer. The subsidiaries included in AGF Investments are AGF Investments Inc. (AGFI), Highstreet Asset Management Inc. (Highstreet), AGF Investments America Inc. (AGFA), AGF Asset Management (Asia) Limited (AGF AM Asia) and AGF International Advisors Company Limited (AGFIA).

AGFA is a registered advisor in the U.S. AGFI and Highstreet are registered as portfolio managers across Canadian securities commissions. AGFIA is regulated by the Central Bank of Ireland and registered with the Australian Securities & Investments Commission. AGF AM Asia is registered as a portfolio manager in Singapore. The subsidiaries that form AGF Investments manage a variety of mandates comprised of equity, fixed income and balanced assets.

More Related Content...

|

|

|