Infrastructure equity as a source of sustainable income

|

Written By: Nick Spencer |

Nick Spencer of Arjun Infrastructure Partners discusses what infrastructure equity can offer investors seeking “Gilts-Plus” investment characteristics

In an enduring low yield and low growth investment environment, many institutional investors are searching for alternative investment opportunities which deliver similar investment characteristics to Gilts, but which offer the additional returns needed to meet future obligations.

Infrastructure is one of the asset classes identified as being a potential source of such opportunities, which we refer to as “sustainable income” investments. This article explores the extent to which infrastructure equity investments represent an attractive source of sustainable income. We will consider:

- The availability of infrastructure assets which offer the desired characteristics

- The risks that investors are taking and whether the achievable returns compensate sufficiently for these risks

- ESG considerations

- Routes to accessing the appropriate infrastructure assets

The available supply of suitable infrastructure assets

A wide range of infrastructure assets offer sustainable income characteristics, i.e. long-term, predictable cash-flows with limited downside risk and including inflation protection. We highlight the following UK-specific examples:

- Renewable energy generation assets

Onshore wind and solar PV generation are the most common technologies found in institutional investor portfolios, but a range of other technologies are also now well established such as offshore wind, energy-from-waste/bioenergy and anaerobic digestion. In the UK, operational assets typically benefit from deriving the majority of their revenues from government-supported mechanisms (renewable obligation certificates (ROCs) or contracts for difference (CfDs)) which offer a stable, inflation-linked cash flow stream - Regulated utilities

Water companies and major gas and electricity networks are probably the most high-profile forms of utility company in the UK. However, other forms of regulated utility also exist which arguably offer a more attractive risk-return profile in the current environment by virtue of being smaller scale and therefore falling below the radar of the larger infrastructure investors. One example is “last-mile” utilities which earn a fixed, inflation-linked, regulated return by operating newly built “last-mile” connections between the electricity/gas grid and domestic or commercial properties - Non-regulated utilities

Companies providing utility services outside of a formal regulatory framework, for example meter asset providers (MAPs). MAPs own the gas and electricity meters in our homes and industrial premises, renting the meters to gas and electricity supply companies (typically highly creditworthy counterparties) under long-term contracts - Transportation infrastructure

Certain forms of transportation infrastructure have limited exposure to demand or volume risk and benefit from long-term, often inflation-linked, contracts. One example is certain train rolling stock companies (ROSCOs), which lease train carriages under long-term contracts - Social infrastructure

Whilst new “greenfield” public-private partnerships (PPPs) or private finance initiatives (PFIs) have largely been halted in the UK, existing PPP assets such as school and hospital buildings remain in high demand due to their long-term, inflation-linked return profiles and high quality public sector counterparties.

The UK has a deep and well-established private infrastructure investment market. Brownfield (i.e. operational) infrastructure asset transactions averaged £18.5 billion per year in the UK between 2015-2018, with an average of 139 transactions per year1. Transaction activity is driven by a number of factors including:

- Developers of greenfield assets looking to sell assets once operational in order to recycle capital to finance new development projects (relevant particularly for renewables assets, the largest sector in terms of number of deals)

- Strategic investors such as utility companies facing capital constraints

- Closed-ended infrastructure funds reaching the end of their fund terms

Taking a forward-looking view, the huge demand for new infrastructure – $94 trillion of investment required globally by 2040, of which $1.8 trillion relates to the UK2 – points to a continued healthy supply of investment opportunities.

In particular, significant infrastructure investment is required to de-carbonise energy and transport systems in order to meet binding climate targets, including the 2008 Climate Change Act which committed the UK to reducing greenhouse gases by 80% by 2050 (compared to 1990 baseline levels). Earlier this year, then-UK Chancellor Philip Hammond estimated the cost to the UK would be £1 trillion by 2050. Globally, the International Renewable Energy Agency estimates around US$26 trillion will need to be invested in low-carbon power generation by 2050.

ESG (environmental, social, governance) considerations

This vast opportunity to invest in the infrastructure required to transition to a low carbon economy highlights the positive environmental and social outcomes that can be achieved through investing in infrastructure. As stated by the UN Principles for Responsible Investment:

“Infrastructure is widely considered to have a positive social impact. Infrastructure forms the backbone of every economy, enabling economic and social development. Increased infrastructure spending is widely considered to generate an economic multiplier effect. Any infrastructure asset, whether under construction or fully operational, generates social, environmental and economic impacts, such as contributing to greenhouse gas emissions reduction, revitalising disenfranchised areas, improving access to services and creating employment. Infrastructure underpins many of the 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and thus infrastructure investors are well positioned to make a positive impact on the societies and economies in which they invest.”

Renewable energy assets are the most obvious example of an infrastructure asset type that can demonstrate a positive ESG outcome, but various other infrastructure sub-sectors also deliver environmental and social benefits. For example, investment into smart meters supports more efficient energy usage, and investing into public transport infrastructure can reduce road usage and improve social mobility.

Risk-return considerations

The risk-return spectrum for infrastructure equity is broad, with targeted nominal IRRs ranging from as low as c.4% for unlevered solar PV and hydro power generation assets in Germany3 through to 15%+ for opportunistic investments more akin to private equity. Unsurprisingly, it is the assets at the lower end of this risk-return spectrum which are most suitable for an investor looking at infrastructure from a sustainable income perspective.

A portfolio comprising the UK-specific example assets described above could be expected to achieve a nominal equity IRR of 5-8% at current market pricing, depending upon the level of leverage applied and the specific risk profile of the individual assets. In an environment of negative real Gilt yields, this represents a substantial premium to fixed income. The question then is whether this return premium compensates appropriately for the additional risks being taken relative to a fixed income investment.

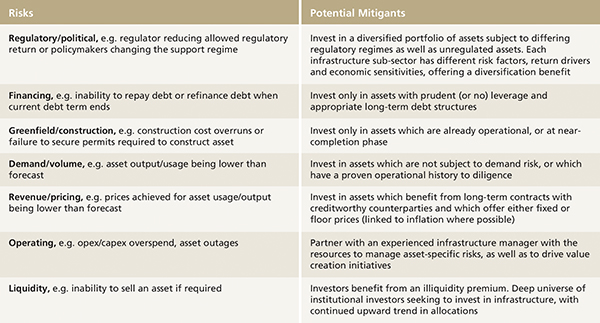

The typical risks faced by an infrastructure equity investor, and potential mitigants are discussed in the table below.

Our view is that the returns available are attractive on a risk-adjusted basis, particularly taking into account the following considerations:

- When we model severe downside scenarios, returns typically remain positive when appropriate leverage is used (even when combining a number of downside scenarios)

- A portfolio diversified by asset type provides important mitigation against the potential impact on the overall portfolio of risks specific to each investment or asset type

- Partnering with an experienced infrastructure manager benefiting from a team with in-house operational and financial asset management capabilities enables asset-specific risks to be appropriately managed and for returns to be optimised through the execution of value creation initiatives

Routes to accessing the appropriate infrastructure assets

The largest institutional investors have the resources to build their own in-house direct infrastructure investment teams, and this model has been successfully implemented by various large institutions in, for example, Canada and Australia. However, for the majority of institutions who do not have access to such resources in-house, the predominant route to gain exposure to infrastructure assets has been via co-mingled “blind pool” limited partnership funds.

The challenge of co-mingled funds for infrastructure is that investors can have requirements and objectives which are unique to them such as risk appetite, required returns and desired duration/hold period. As a limited partner in a co-mingled fund does not control these key decisions, it can be difficult for an investor to find a fund which delivers on their specific requirements and have confidence that this will remain the case over the life of the fund.

Thankfully, alternative solutions do exist in the form of managers who offer bespoke investment mandates allowing each investor to control key decisions such as investment selection/portfolio construction and desired hold period. Such bespoke structures therefore offer investors the opportunity to achieve a much better match against their objectives than a co-mingled fund structure.

Conclusion

A portfolio of carefully selected infrastructure equity investments can be constructed to deliver a source of sustainable income, i.e. long-term, predictable cash-flows with limited downside risk and including inflation protection. An additional ESG benefit can be secured by focusing on infrastructure assets delivering positive environmental and social outcomes.

In order to harness the maximum benefit from such investments, a bespoke investment mandate allowing the individual investor to control key decisions such as investment selection and desired hold period may offer a better solution than investing in infrastructure via co-mingled blind pool funds.

1. Infradeals database

2. ‘Global Infrastructure Outlook’; Oxford Economics & Global Infrastructure Hub

3. ‘Renewable energy discount rate survey results – 2018’; Grant Thornton

More Related Content...

|

|

|