Navigating the ESG landscape – the times are a-changing for the LGPS

|

Written By: Paul Myles |

|

Vicki Bakhshi |

last year’s new government guidance, in addition to pooling, is moving the goalposts for local authorities as they look to implement robust ESG Strategies. Paul Myles and Vicki Bakhshi of BMO Global Asset Management look at the options available for the LGPS

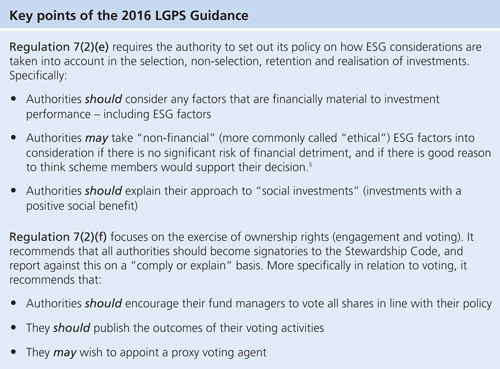

The government’s September 2016 statutory guidance on Investment Strategy Statements¹ set out in more detail than ever before what is expected of the LGPS in relation to Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) policies. Of the six sections of the guidance, two relate specifically to ESG – one in relation to how ESG fits into investment selection and monitoring, and one on stewardship activities.

All 89 England and Wales funds have now produced their new Investment Strategy Statements (ISSs) in line with the guidance, with all statements referencing ESG policies. But the story doesn’t end there. The guidance left space for interpretation – with the position further complicated by an ongoing legal challenge. The 89 statements vary widely in their position and level of detail on ESG policies, and many of the tough questions will only arise when it comes to implementation.

What are the expectations on ESG for local authority funds?

The 2016 guidance for local authorities is consistent with, and draws heavily from, two sources: the 2014 Law Commission report, which dealt with the question of how ESG matters are consistent with fiduciary duty²; and the UK Stewardship Code, which lays out expectations for how investors should monitor their investee companies and exercise their ownership rights.³

Subsequent to the LGPS guidance being published, a further key development has been the issuance by The Pensions Regulator of ESG guidance for Defined Benefit schemes, which is applicable to local authorities.⁴

How does ESG square with fiduciary duty?

The question of how taking ESG factors into account fits with fiduciary duty has been one of the most extensively discussed in the responsible investment industry. In the UK, the legal position was established by the Law Commission’s 2014 report, which the LGPS guidance mirrors.

The guidance differentiates between “financial” and “non-financial” ESG factors. Simply put, the starting point for authorities is to think of ESG factors in exactly the same way as more “traditional” factors such as macroeconomic developments – as something that may affect investment returns. This may either be as a risk – as evidenced by the numerous examples of poor governance, corruption or environmental catastrophe that have damaged shareholder value – or as an opportunity, if authorities take the view that investing in potential growth sectors such as clean tech may help generate alpha. Looking at ESG in this sense is something the guidance makes clear that authorities should do as an integral part of their fiduciary duty. In practice, for outsourced investments this will be implemented as part of manager monitoring and selection, by asking detailed questions about the way such financial risks and opportunities are incorporated into investment analysis.

The guidance on “non-financial” factors effectively means that authorities can take ethical stances in relation to their investment, including divestment of controversial companies such as tobacco companies or fossil fuel producers, but only if two tests are met – that there is not “significant risk of financial detriment”, and that there is “good reason” to think that scheme members would support their decision. Meeting these tests requires an understanding of the portfolio impact of any divestment action. Most authorities have historically taken a cautious view, based in part on the Cowan vs. Scargill⁶ trust law case where the conclusion of the Mineworkers’ Pension Scheme case stated that that pension scheme trustees should largely put aside their own moral and ethical principles when investing pension scheme assets. However, this case was over three decades ago; newer industry and academic research indicates that ethically-screened and mainstream funds can and do perform in line over the long term⁷, the implication being that a carefully-chosen divestment approach can be followed without an expectation of financial detriment.

Are local authority ESG policies expected to align with central government objectives?

The most controversial area of the original guidance related to the question of whether, and how, local authority investment strategies should align with the government’s foreign and defence policies. The original guidance stated that “using pension policies to pursue boycotts, divestment and sanctions against foreign nations and UK defence industries are inappropriate other than where formal legal sanctions, embargoes and restrictions have been put in place by the Government.” This effectively would have prevented local authorities from taking an ethical stance to divest holdings in, for instance, companies whose activities are alleged to be supporting the development of Israeli settlements in Palestine. In June this position was found to be unlawful, though the government plans to appeal, and the legal position therefore remains uncertain.

More subtle, but potentially far more significant from a financial point of view, is the question of whether funds should be expected to contribute to the government’s wider social agenda, through directing capital towards investments with a positive social benefit: “social investments”. The guidance differentiates between those that make financial sense in their own right, and those which may involve a trade-off where, as with ethical stances, extra tests must be met.

In practice, authorities seeking investments with demonstrable positive benefits to the UK’s social goals, particularly in private asset classes such as infrastructure, have to date found the choices limited given a realistic minimum investment size. Choices open up much more when it comes to identifying public market investments, where a growing number of managers – including BMO Global Asset Management – are now developing methodologies to systematically report on the positive impact of their investments in areas such as health, sustainable energy and green finance.8

How are expectations on stewardship evolving?

The Stewardship Code, to which all authorities are encouraged to report against, sets out seven principles for good stewardship, covering policy development, engagement, voting and disclosure. The Financial Reporting Council has been working on ratcheting up implementation by signatories and recently ranked signatories into tiers – with some authorities falling into the “best practice” tier 1, and others into tier 2, indicating some shortcoming in disclosure or policy.

In terms of implementing Stewardship policies, a key challenge is that engaging with companies in the impactful way laid out in the Stewardship Code is highly time-intensive. Some local authorities undertake their own engagement, usually through collaborative groups such as the Institutional Investors Group on Climate Change; others delegate to their managers as part of Investment Management Agreements, or to a specialist engagement service provider – many being represented by the Local Authority Pension Fund Forum, while BMO Global Asset Management, amongst others, also provide specialist engagement services. Using a service provider has the advantage that authorities can work with the provider to feed in their own ideas and priorities.

One of the more challenging questions has been around the exercise of voting rights – and in particular, whether funds that are invested, for cost reasons, in pooled investment vehicles such as OEICs can express their own governance beliefs through instructing their managers to vote in a particular direction at company AGMs. Although in principle this sounds appealing, in practice it can be administratively complex for asset managers to administer, and few are prepared to countenance it. There is, however, certainly a role for the LGPS – including, in future, the new pools – to monitor how asset managers are implementing their voting rights, and to press for greater transparency where this may be lacking.

How should funds approach the issue of climate change?

Many local authorities have faced intense pressure from NGOs to consider divesting fossil fuels, and most recently the NGOs ShareAction and ClientEarth asked the Pensions Regulator to consider the issue, citing the fact that only 12 of the new ISSs have any specific mention of climate change.⁹

This is part of a wider global investor debate about how investors should respond to the potential systemic risks posed by climate change and the low-carbon energy transition, the latest development in which has been the publication of the final report of the Taskforce on Climate-related Financial Disclosures, a high-level industry group set up by Bank of England governor, Mark Carney, to explore how corporates and investors should monitor and manage climate risk.

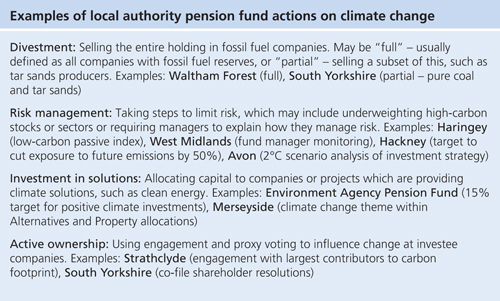

At BMO Global Asset Management, we have seen investor responses fall into four categories: divestment, risk management, investment in solutions and active ownership. None are “right” or “wrong” and many investors are using them in combination. For instance, BMO Global Asset Management’s Responsible Funds use all four strategies, with divestment of fossil fuel producers, risk management for energy-intensive sectors, positive investment in solutions and proactive engagement with management.¹⁰

Looking forward

In the short term, the main task at hand in relation to ESG policies is to move from statements of intent in the Investment Strategy Statements to practical implementation at the mandate and portfolio level. The successful achievement of this will require joined-up actions at both the individual fund level and by the new pools. A key challenge for the pools will be to understand and interpret the varied ESG statements of individual authorities, and translate these into credible and consistent investment approaches that fairly represent them, in relation for instance to their evaluation of the efficacy and quality of ESG performance of managers as part of their manager selection, and portfolio monitoring responsibilities.

For funds themselves, the focus will shift to longer-term investment strategy, strategic asset allocation, and risk management. ESG and climate change policies should not be considered an “add-on” to these core functions, but rather as a set of tools that can help to achieve them, through enhanced management of long-term risks and opportunities. Additionally, as beneficiaries are increasingly expressing an interest in funds being invested responsibly¹¹, adopting and implementing proactive and progressive ESG strategies can help both funds and the asset pool managers to anticipate their future needs too.

Important information

For professional investors only. The value of investments and income derived from them can go down as well as up as a result of market or currency movements and investors may not get back the original amount invested. Past performance should not be seen as an indication of future performance.

Views and opinions have been arrived at by BMO Global Asset Management and should not be considered to be a recommendation or solicitation to buy or sell any products that may be mentioned.

© 2017 BMO Global Asset Management. All rights reserved. BMO Global Asset Management is a trading name of F&C Management Limited, which is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. F&C Management Limited accepts no liability for any loss arising from the use of this article, nor make any representation as to the accuracy or completeness.

1. Local Government Pension Scheme: Guidance on preparing and maintaining an investment strategy statement, DCLG, 2016

2. Fiduciary Duties of Investment Intermediaries Report, Law Commission, 2014

3. The UK Stewardship Code, Financial Reporting Council, 2012

4. Investment guidance for defined benefit pension schemes, The Pensions Regulator, 2017

5. Following a successful legal case against the government in June 2017, previous text barring local authorities from pursuing political boycotts has been removed

6. Scargrill et al. wanted the scheme to cease overseas investment and investments which directly competed with coal

7. See, for instance, Sustainable Reality, Morgan Stanley, 2015, which reviews the performance of 10,000 US SRI and non-SRI mutual funds

8. Responsible Global Equity Strategy: ESG Profile and Impact Report 2017, BMO Global Asset Management, 2017

9. Referral to the Pensions Regulator, ShareAction and Client Earth, February 2017. The Pensions Regulator rejected the referral

10. BMO Responsible Funds and the Transition to a Low-carbon Economy, BMO Global Asset Management, 2017

11. See, for instance, UK Sustainable Investment and Finance Association’s Good Money survey, where 54% of individuals said they would like their pensions to have a positive impact beyond just making money

More Related Content...

|

|

|