Rates are rising, but is it sustainable?

|

Written By: Jim Cielinski |

Jim Cielinski of Janus Henderson Investors explores the steep rise in bond yields, the prospects for inflation and the implications for fixed income asset allocation

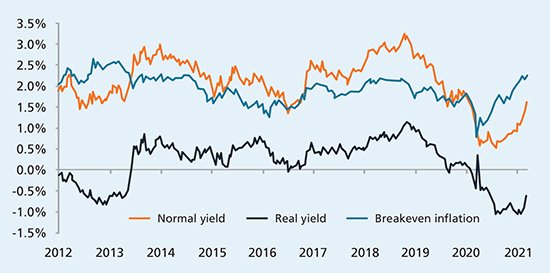

The bond market has awoken from its slumber. What began as a gradual climb in nominal yields from the summer, accelerated in February and March, with the yield on the US 10-year Treasury topping 1.7% in mid-March, with significant moves also seen in Australia and the UK. This is a rise of more than 100 basis points (bps) from the lows reached in 2020. Deciphering the move in the chart below, a few things are clear. First, the move retraces an even faster decline in yields a year ago when markets (rightly) feared a global economic collapse induced by Covid-19. Second, while the initial move upward was led by higher breakeven inflation reaching 2.3%, in recent weeks this has stalled and been followed by higher real yields, which have moved off the lows.

Figure 1: US 10-year Treasury, real yield and breakeven inflation

Source: Bloomberg, 6 January 2012 to 12 March 2021, as of 15 March 2021.

Despite the sharp rise in yields, credit markets were not spooked. Corporate credit indices, by and large, saw spreads tighten in February, though they began to widen in March. Credit markets tend to be more sensitive to spikes in volatility. They also tend to correlate more highly with equity markets, and global equity markets were on the surface unnerved (with the S&P 500 Index still close to all-time highs). However, this does mask severe rotation within equities, with cyclicals and value equities rallying and growth and defensives underperforming.

A healthy correction?

The lows that 10-year US Treasuries reached last summer reflected fears that a synchronised global economic shutdown could cause historic economic damage. Caution was king. Yet 10-year bond yields began climbing from the summer as investors considered the possibility of a Democratic-led government in the US leading to additional spending. Positive vaccine news in November meant investors could debate the when, not the if, of economic recovery. By February, the reflation narrative was consensus. US Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell described the move towards higher yields as a statement of confidence in the economy. It is also a mechanical result of flexible average inflation targeting (FAIT) as the Fed is prepared to tolerate inflation above target as it holds short-term rates low.

Regime change for inflation?

Central banks are being challenged. We will likely get an inflation upswing in coming quarters – the key for markets is whether this is temporary or persistent. Year-on-year inflation is expected to rise quickly as a result of the low base set in 2020 due to the pandemic, but it is harder to argue this is a precursor to a new regime of structurally higher inflation. Despite (perhaps excessive) fiscal and monetary stimulus, unemployment remains high, and the output gap is wide; it will take time to sufficiently reduce both to the point where they threaten inflation.

We think inflation will peak in the US this spring. The base effect from 2020 lows should push it sharply higher, then rapidly fade. In our view, consumption, will act similarly. Pent-up demand for goods and services could see a consumption surge, but inflation is a rate of change index, and this pent-up demand is arguably a one-off.

Dig deeper and a range of regional Fed inflation measures currently indicate underlying inflation measures are trending weaker.¹ This could change, but it reinforces the idea that the Fed has no reason to respond and that inflation would need to move above 2% and stay there to meet their criteria to begin hiking rates under their new average inflation targeting regime.

Are markets too optimistic about the economy?

Economists have over-predicted inflation for more than a decade, but the new US fiscal policy regime may spark fears of a modern monetary theory (MMT) style game-changer. This is the first time fiscal and monetary policy are working in tandem – does that change the secular stagnation narrative? Risk of a “surprise” is probably greater in the US due to larger fiscal spend, huge Treasury supply and a higher potential growth rate compared to other developed economies. We fully expect a short-term sugar rush, as there will be some revenge spending by consumers (think holidays and haircuts), but this will be time limited.

More generally, the fiscal multiplier may be low because excess savings have mostly been accumulated by the top 20% of income earners, who have a lower marginal propensity to consume. The world’s developed economies will exit this recession with substantially higher debt levels than even 12 months ago. Debt financed spending, rather than investment (aside from the Biden infrastructure plans), does not typically increase the productive capacity of an economy over the long term. In already highly indebted economies, the (low) marginal productivity of this debt has acted as a gravitational pull downwards on government bond yields.

Finally, consensus forecasts show the US as the only developed economy likely to see complete economic recovery from the Covid-19 crisis by the end of 2021. Much of Europe and Japan are not expected to see a full recovery before even the end of 2022. Past periods of dramatic reflation driven by China’s rise are unlikely to be repeated due to the growing maturity of the Chinese economy. Additionally, with the China credit impulse rolling over, this may suggest a slowdown into 2022, where all of this will be combined with the negative base effect of a fiscal cliff as stimulus rolls off.

What could spark disorder?

Central banks have, so far, tolerated the rise in long-term bond yields, seeing the move as a sign of improving economic sentiment. At the same time, markets are having to price some genuine uncertainty in balancing the unknowns regarding the scarring of the pandemic, which we believe are likely underestimated, against the unprecedented fiscal spending boost and elevated bond supply (particularly in the US), requiring a greater risk premium.

But when does a rise in bond yields go from good news to bad? We believe this has to do with both the pace and the cause. Central banks would be concerned if they saw more disorderly and correlated markets (like March 2020), or a persistent tightening in financial conditions due to higher real rates. While real yields remain negative, the Fed is likely to remain sanguine, but it will not want to see a repeat of the taper tantrum of 2013. Higher real rates not only increase costs of debt finance but also have knock-on effects on credit spreads and equity market valuations, which tighten financial conditions. A rise in real yields may end up being self-limiting, if it feeds through to a significant correction in risk assets.

What does this mean for asset allocation?

In our view, the fundamental environment remains positive for credit markets. The outlook for economic recovery has improved and many companies are in the early stages of balance-sheet repair. The expected backdrop of strong global earnings growth, boosted by accommodative monetary and fiscal policies, sets an unusually supportive scene for risk assets. Against this positive fundamental backdrop looms expensive valuations. Current prices, and spreads, have already priced in the improving economic environment, particularly in investment grade, where spreads are tight.

Vaccines offer a clearer path out of the pandemic and should boost the most troubled economic sectors, offering some opportunities within credit markets to position for further spread compression between COVID losers and winners and lower credit quality versus higher-rated debt. The high-yield market offers lower interest rate duration than investment-grade corporates, while its higher yields offer greater cushion against losses driven by rising interest rates. Short duration is also offered within the asset-backed securities (ABS) market, and floating-rate securities such as collateralised loans obligations (CLOs).

Additionally, longer maturity bonds in some markets (ex Germany and Japan) are back to levels that offer better prospects as a risk-off hedge. With longer maturities leading the sell-off, term rates have normalised closer to their long-run expected level (e.g., the US five-year rate five years forward swap rate is close to 2.5%). Unless a regime shift is underway, and central banks move to hike rates well ahead of current guidance, it is hard to envisage the pace of rise in government bond yields that we saw in February and March being sustained.

Important information

This article is intended solely for the use of professionals, defined as Eligible Counterparties or Professional Clients, and is not for general public distribution. For promotional purposes.

The views presented are as of the date published. They are for information purposes only and should not be used or construed as investment, legal or tax advice or as an offer to sell, a solicitation of an offer to buy, or a recommendation to buy, sell or hold any security, investment strategy or market sector. Nothing in this material shall be deemed to be a direct or indirect provision of investment management services specific to any client requirements. Opinions and examples are meant as an illustration of broader themes, are not an indication of trading intent, are subject to change and may not reflect the views of others in the organisation. It is not intended to indicate or imply that any illustration/example mentioned is now or was ever held in any portfolio. No forecasts can be guaranteed and there is no guarantee that the information supplied is complete or timely, nor are there any warranties with regard to the results obtained from its use. Janus Henderson Investors is the source of data unless otherwise indicated, and has reasonable belief to rely on information and data sourced from third parties. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Investing involves risk, including the possible loss of principal and fluctuation of value.

Not all products or services are available in all jurisdictions. This material or information contained in it may be restricted by law, and may not be reproduced or referred to without express written permission or used in any jurisdiction or circumstance in which its use would be unlawful. Janus Henderson is not responsible for any unlawful distribution of this material to any third parties, in whole or in part. The contents have not been approved or endorsed by any regulatory agency.

Janus Henderson Investors is the name under which investment products and services are provided by Janus Capital International Limited (reg no. 3594615), Henderson Global Investors Limited (reg. no. 906355), Henderson Investment Funds Limited (reg. no. 2678531), Henderson Equity Partners Limited (reg. no.2606646), (each registered in England and Wales at 201 Bishopsgate, London EC2M 3AE and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority) and Henderson Management S.A. (reg no. B22848 at 2 Rue de Bitbourg, L-1273, Luxembourg and regulated by the Commission de Surveillance du Secteur Financier).

Janus Henderson, Janus, Henderson, Perkins, Intech, Knowledge. Shared and Knowledge Labs are trademarks of Janus Henderson Group plc or one of its subsidiaries. © Janus Henderson Group plc.

1. Source: Bloomberg, Dallas Fed Trimmed Mean, Fed Core Sticky, 31 December 2007 to 31 January 2021, as of 15 March 2021.

More Related Content...

|

|

|