The great transition

|

Written By: Martin Grosskopf |

The obligation to build a more sustainable economy has never been greater. Martin Grosskopf of AGF Investments looks at what it means for investors

The economic and social toll wrought by Covid-19 over the past year and a half is without question. Government lockdowns to control its spread caused one of the deepest and most abrupt global recessions in modern history. But the disease’s long-term impact on society and financial markets may end up being even greater as it relates to its influence on how we deal with other systemic problems such as climate change. The pandemic has shone a brighter light on the magnitude and urgency of our environmental and social ills, and has reinforced the need for government, investors and corporate leaders to direct capital more effectively at enterprises that offer solutions to these complex issues.

Of course, in doing so, it has become that much harder to envision an investment landscape that does not end up being markedly different than it is today. Accelerating the transition of capital towards activities and business models that embrace sustainability and resilience will likely dictate market returns in the years ahead.

The best starting point for understanding all of this is the Paris Accord of 2015. It was there and then that governments from around the world agreed to limit global warming to at least two degrees Celsius – if not less – and set a goal of zero net emissions (i.e. absorbing the same amount of carbon as emitted) by 2050. At its core, the agreement is grounded in the science of climate change and is designed to avert many of the worst-case scenarios that would otherwise be associated with potential weather disasters in the future.

But the past year and a half has demonstrated that in order to have any reasonable chance of meeting this 2050 objective, the scale of emissions reduction is almost unfathomable.

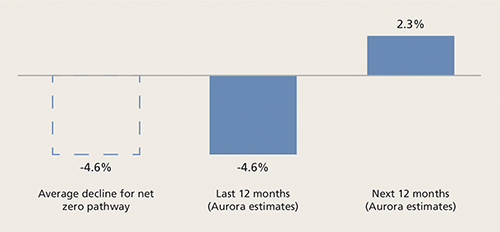

For example, the Covid-induced lockdowns resulted in only a 4-5% reduction in global carbon emissions. This level of reduction would be an annual requirement moving forward in order to meet the 2050 zero net emissions long-term objective.

Figure 1: Annual change in total global emissions

Source: UBS Research, as of September 2020

Although this seems improbable in practice, its daunting magnitude demonstrates the urgent need for increased regulatory action. Led by the European Union’s Green Deal, for instance, governments around the world have begun targeting stimulus, first, at “green“ activities such as renewable energy, electric vehicles and building efficiency, but then also increasingly at so-called “transition“ activities. This latter target is much larger than the former and encompasses carbon-intensive industries which may or may not survive in a green economy. These include industries that are so integral to our day-to-day life they cannot simply be shut down and must instead be transitioned towards lower emissions, requiring a re-engineering of entire supply chains and production processes.

As investors, issuers and lenders begin to appreciate the scope of the change required, the opportunities have become just as important as the risks. As we have long proposed, capital incentivised by governments will begin to flow towards more sustainable activities and away from those with large environmental footprints. These flows will accelerate due to the fear of unmitigated climate change, but also in a relative race for technology leadership in the fields of renewables, batteries, electric vehicles, building efficiency, hydrogen and biomaterials.

These are areas of transition that one might expect an expert in sustainable finance to highlight. After all, they are specifically environmental in nature and perhaps predictable. However, Covid-19 also lays bare other social arenas in full transition.

The shift in balance of power from shareholder to governments was underway prior to the pandemic, but US$12 trillion of global stimulus – according to the International Monetary Fund – has made obvious the inability of markets to direct capital in a fashion that would provide resiliency in the face of a major natural disaster or similar health crisis. Meanwhile, in a little over a decade since the financial crisis of 2008, increased government intervention in the form of helicopter money and the seeds of a universal basic income (theoretically temporary in nature, but more likely than not to be revisited in the next crisis) now seems to have been inevitable.

Certainly, little of the funding to date addresses the root causes of the pandemic – i.e. a virus that was passed from animal to human (like 60% of the more than 1,400 known infectious diseases can be, according to May 22 article in Foreign Affairs magazine) – which in turn provides ample runway for investments that do – as well as those that help build resilience to deal with the consequences. The interaction between food insecurity, environmental degradation and pandemic spread is a ground well trodden by scientists and addressed directly by the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) which are providing a longer-term road map for governments and investors. In fact, between 2014 and 2019, the population experiencing some form of food insecurity increased from 22.4% to 25.9% according to the World Health Organisation. That’s a surprising statistic given the SDGs were launched in 2015, but highlights how the pandemic exposed the fallacy that protectionism can truly isolate citizens from the responsibility of acting and investing with a global mindset.

Transition in this context might also describe the pension system as it adjusts reluctantly to historically low interest rates and the implication of reduced returns. Systemically higher unemployment coupled with a higher savings rate and lower returns are pressures unlikely to be mitigated by the relentless increases in passive allocations in a period of zero discount rates.

Similarly, post-Covid views of retirement embedded in some interpretations of fiduciary responsibility will surely need to change. Retirees are among the most vulnerable to the globalisation of health and environmental risks. A narrow definition of financial health that is based on certainty of income can not compensate for risk to assets (retirement properties, etc.) or health (air quality, pandemic etc).

Clearly then, our transition to a more sustainable economy is no simple task and, in all its forms, will require new thinking, fresh capital, more risk-taking and increased urgency if it’s to be successful. Perhaps it took the tragedy of a global pandemic to teach us that and bring truth to the phrase “let no crisis go to waste”.

The commentaries contained herein are provided as a general source of information based on information available as of August 18, 2021 and should not be considered as investment advice or an offer or solicitations to buy and/or sell securities. Every effort has been made to ensure accuracy in these commentaries at the time of publication, however, accuracy cannot be guaranteed. Investors are expected to obtain professional investment advice.

AGF Investments is a group of wholly owned subsidiaries of AGF Management Limited, a Canadian reporting issuer. The subsidiaries included in AGF Investments are AGF Investments Inc. (AGFI), AGF Investments America Inc. (AGFA), AGF Investments LLC (AGFUS) and AGF International Advisors Company Limited (AGFIA). AGFA and AGFUS are registered advisors in the U.S. AGFI is a registered as a portfolio manager across Canadian securities commissions. AGFIA is regulated by the Central Bank of Ireland and registered with the Australian Securities & Investments Commission. The subsidiaries that form AGF Investments manage a variety of mandates comprised of equity, fixed income and balanced assets.

™ The “AGF” logo is a trademark of AGF Management Limited and used under licence.

More Related Content...

|

|

|