The profit pool – a less dynamic landscape favours the corporate giants

|

Written By: Subitha Subramaniam |

Subitha Subramaniam of Sarasin & Partners discusses the growth of corporate profits in the past few decades, and their outlook in a period likely to be characterised by higher taxes and slowing revenue growth

The last few decades have provided a golden era for corporate profits. Globalisation opened up new markets, even as wages, taxes, borrowing costs, and the cost of equipment fell sharply. A remarkable confluence of forces benefited both the top and bottom line of global companies.

In a recent study, the McKinsey Global Institute estimated that between 1980 and 2013, earnings before interest and taxes tripled in real terms. As a share of global GDP, the profit pool increased from 7.6% to 9.8%. Can such stellar growth continue?

The top line

Corporate revenues are inextricably linked to global GDP growth, which since 1980 has increased by 3% per annum on a real basis. This renaissance in global growth has been driven by a pickup in the world’s labour force, the pace of emerging market catch-up, and the pace of technological advance.

Many of these tailwinds are set to fade. Not only is the pace of population growth projected to decline in the coming decade, but the bulk of growth is expected to come from poorer parts of the world – from countries like Nigeria, Ethiopia, Bangladesh and Pakistan – which have repeatedly struggled to harness their growing populations in a productive manner. The world’s population will also be materially older, and economies will depend heavily on the increased participation of older workers. Demographic trends suggest that, at best, the world’s labour force will contribute 1% per annum to global growth over the coming decade.

Further, productivity growth across the developed world has stalled in recent years. There are structural forces at play here – economic structures have shifted towards services, where productivity is difficult to measure (it is difficult to improve the productivity of a haircut, restaurant meal or musical performance). The rise of the free economy in virtual information, communication and entertainment services (displacing physical newspapers, maps, encyclopaedias, and long-distance telephony) is also suppressing productivity. Free goods may improve the quality of our lives (“consumer surplus”), but for GDP and profits they reduce transactions and lower productivity.

And on the heels of rapid Chinese growth over the past two decades, it is becoming abundantly clear that China’s growth will be materially slower in the decade ahead. A slower China will inevitably lead to slower growth in other emerging markets, where economies have become much more intertwined with that of China. We therefore expect a slower pace of emerging market catch-up in the coming decade.

Weighing up these demographic and productivity trends suggests that GDP growth will likely slow by a third over the coming decade. Corporate revenues should mirror this downward shift in global GDP, growing at a pace of 2% per annum in real terms.

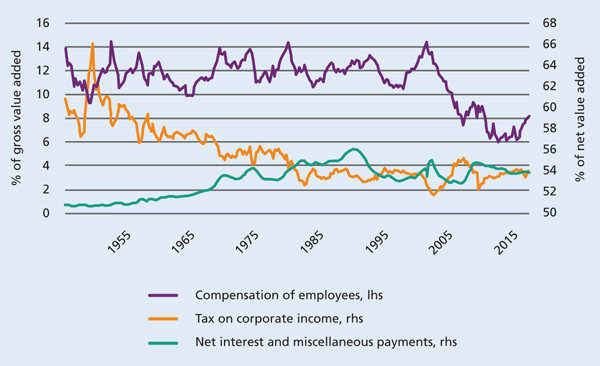

Figure 1: Compensation, taxes and net interest as a percentage of corporate income

Source: Macrobond

The bottom line

Not only did globalisation expand the market place for multinationals, giving them a vastly expanded revenue pool, it was accompanied by a decline in corporate taxes, interest payments and wage costs that heaped extraordinary benefits on firms’ bottom lines. Figure 1, which plots the trend in key cost components as a proportion of corporate revenue for US companies, shows a simultaneous decline in firms’ key expenses.

Let us examine each of these in turn.

Employee compensation is the biggest expense for businesses, typically accounting for roughly 63% of revenues. Over the last decade, however, compensation as a share of total revenue has been steadily falling, driven by increased integration of emerging market labour into global supply chains, the shrinking power of labour unions and increased automation of production. Stagnant wages for lower skilled workers is now leading to a social and political backlash. There is clearly scope to accommodate some rise in wages, which can have a positive impact on growth and profits, given lower wage earners’ greater prosperity to spend.

Corporate taxes as a share of corporate revenue are also extraordinarily low. Effective tax rates for publicly listed companies in advanced economies have dropped from 43% in 1993 to roughly 31% today. The substantial disparity in tax rates across countries has also created many opportunities for global tax arbitrage. However, as tax fairness rises up the political agenda, it is likely that the corporate tax burden will increase in the coming years.

Meanwhile, as borrowing costs steadily declined over the past 30 years, interest burden of corporates fell. US companies have largely been taking advantage of low-cost financing to conduct mergers and acquisitions (M&A) and share buybacks: the pace of M&A is more than twice what it was in the 1990s, while the number of listed companies almost halved between 1997 and 2013. Had corporates not levered up their balance sheets, their interest burden might be lower still.

Competitive landscape

Profits are highly dependent upon the structure of the market place. Highly competitive market places erode profit margins, while more consolidated market structures tend to experience persistence in profits.

Over the past decade, the structure of US industry has become more consolidated, suggesting that profits might be more persistent than in previous cycles. Concentration ratios across many industries have been rising; the share of GDP generated by America’s 100 biggest companies has risen from 33% in 1994 to 46% in 2013; the five largest banks account for 45% of banking assets (25% in 2000) and sales of the median listed public company is almost three times as big as it was 20 years ago.

Concentration is particularly visible in the technology sector, where giants like Alphabet, Amazon, Facebook, Alibaba and Tencent have reached “hyper scale” in revenues, assets, customers, workers and profits. As their digital platforms drive down the marginal cost of storing and transporting data, digital operators are adding new business lines quickly, bringing with them “hyper scale” advantages and dynamics. Technology giants have made rapid moves into adjacent sectors, from finance and publishing to cloud and logistics, and from mobile operating systems to autonomous driving.

What’s more, globalisation lends itself to larger and more integrated market players.

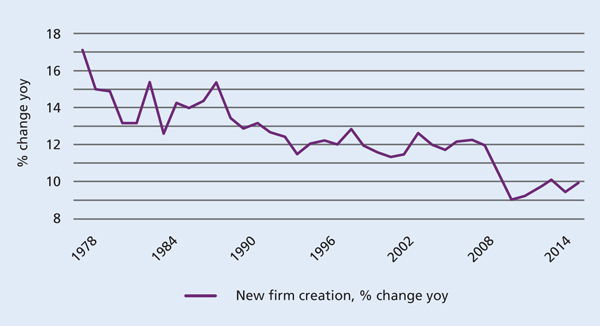

There are signs that scale is becoming a barrier to entry. Figure 2 shows that there has been a dramatic decline in the pace of new firm creation in the past eight years in the US. Despite the constant drumbeat of “unicorns” (start-up companies valued at over $1 billion), the reality is that most start-ups are finding it harder to get off the ground. Low interest rates are not enough to jump-start business dynamism. Scale, economic moats and regulation are becoming substantial barriers to entry.

Figure 2: New firm creation, percentage change year on year

Source: Macrobond

What is the outlook for corporate profits?

Structural headwinds in the form of weaker global growth mean that the growth of revenue pools will also be slower in the decade ahead. Tax fairness will gain in importance, putting upward pressure on corporate taxes. Wage bills are also likely to face upward pressure, but the modest increases pencilled in for low-skilled workers may not be negative for long-term growth and hence profits. However, given the backdrop of sustained repression of interest rates by the world’s central bankers, the interest burden for corporates is unlikely to materially increase. Higher taxes and slowing revenue growth are therefore the probable key drivers of weaker profits growth.

Still, while the golden era for corporate profits has likely come to an end, industry consolidation suggests that the profit pools of giant companies could sustain themselves in a more challenging environment. In many ways, scale is becoming a moat, and as concentration ratios rise across industries, a less dynamic landscape is likely to prevent their profits from being competed away.

More Related Content...

|

|

|