Is it time to go floating rate?

Comment

|

Written By: Bernard Abrahamsen |

As fixed income investors we’ve always been concerned about volatility, and it’s been a central feature of bond markets since the Lehman crisis. As the financial headlines have swung from bailout packages and sovereign defaults to debt ceilings and banking woes, on-going volatility has been the one entirely predictable thing about today’s financial markets. Recently, as the global economy has shown signs of improving, another driver of volatility, the potential return of higher interest rates, has reared its head.

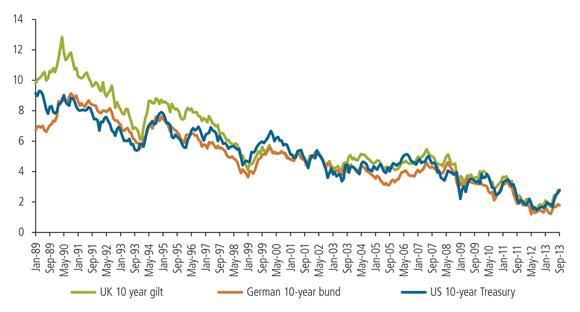

As we all know, today’s interest rates are almost as low as they can go. In the UK, the official rate is 0.5%, the lowest since records began in 1694. Meanwhile, bond yields have been falling for 25 years, as Figure 1 shows. Rates certainly won’t go up today, or tomorrow; they might not even go up next year, but at some point interest rates will go up, the only question is when.

Why should this concern fixed income investors? Because risk free fixed-rate bond prices are inversely related to interest rates – i.e. when rates go up, those bond prices go down.

To what extent can rate rises hurt fixed income portfolios?

How much the value of a bond, or indeed a bond portfolio, is affected by changes in interest rates is measured by something called “duration” or interest rate risk. If your portfolio has a duration of eight for example, then a 1% rise in interest rates will likely cause your portfolio to fall in value by 8%.

This is partly why the market is so worried about rates going up. Earlier this year, in May, the US Federal Reserve expressed its potential intent to scale back its quantitative easing (QE) operations. Such an act would have been little more than a baby step towards actually raising rates but nonetheless investors panicked. June was the third worst month on record for sterling credit, and sixth worst for euro credit. But despite this, some bond portfolios ended the month unscathed. How? By running no interest rate risk at all – their duration measure was zero.

Figure 1. Government bond yields (%)

Source: Bloomberg, 30 September 2013

Protecting your bond portfolio with floating rate cash flows

How is it possible to run a fixed income portfolio with no duration? One way is to hedge the interest rate risk of your fixed-rate assets, and another is to buy floating-rate rather than fixed-rate assets. Unlike their fixed-rate counterparts, a floating-rate bond’s coupons change when interest rates do. So if rates increase, so does the coupon – providing invaluable protection for bond investors in a rising interest rate environment.

Are all pension schemes concerned about duration risks?

Not necessarily – it’s true that some pension schemes don’t need to worry about interest rates. If rates rise, the value of their liabilities will decrease in line with the value their fixed income assets. That means even though the scheme would stand to lose money on their bonds if rates rise, it won’t affect the scheme’s ability to pay its pensioners.

That being said, these schemes might still want to consider the benefits of running no duration risk at this time, just because they will avoid the risk that the value of their assets will fall significantly. What’s more, if a scheme is running a deficit, it would surely be ill-advised to risk losing a great deal of money on their bond holdings.

So, what are some examples of floating-rate assets? While several investment grade and high yield corporate bonds offer floating-rate structures, there are entire fixed income asset classes which exclusively pay floating rates of interest. Let’s highlight two examples:

1) Asset-backed securities (ABS)

ABS bonds are a classic example of floating-rate instruments. Not only do they offer protection against rising interest rates, they offer several other advantages. Investors benefit from security against certain assets, such as mortgages or credit card loans. Furthermore, the bonds are typically structured to be “bankruptcy remote” from the originating bank, meaning that should the bank in question go bust, it will not directly affect the security’s ability to pay out its promised cash flows to the owner of the asset.

Despite their relative safety, returns are attractive on ABS bonds for two main reasons. First, ABS bond structures are not standardised, and even a single issuer’s own bonds can vary greatly in terms of structure. They need to be thoroughly analysed and so only those who have the capacity and expertise to do so have any hope of accurately determining a security’s value. This means only a limited number of investors are able to participate in the market, and thus can demand higher returns.

Secondly, many investors associate all ABS with the US subprime crisis of 2007, so they demand higher returns across the entire sector. However, according to our ABS credit analysts, the best bonds can withstand a huge amount of economic pain.

To demonstrate: imagine a world where UK house prices fell 55% from their peak level and consumer mortgage defaults rose to 11% pa. for three years before reverting to 2.1% p.a. indefinitely (keep in mind that the highest repossession rate of all time in the UK was just 0.8% pa. in 1992). Under this scenario, our models show that the very strongest ABS bonds will still be robust enough to be able to pay their cash flows.

If this scenario actually happened in real life, it’s probably safe to say every bank would likely have gone bust, unemployment would probably have hit 40% and Britain itself could have gone bankrupt. An Armageddon-type situation such as this is hard to fathom, but if things were to get this bad, the best ABS bonds would certainly look risky. However, given the damage that would have been caused to investors’ other assets, that would probably not be their most pressing concern.

2) Commercial real estate debt

This is yet another asset class able to provide senior and secure floating-rate cash flows. Senior mortgage loans are the safest type of real estate debt, offering credit risks similar to an A- rated corporate bond, but generally with higher returns and the benefit of security against the underlying real estate. They are typically lent at loan-to-value (LTV) rates of around 55%. This means that even if the borrower defaults, the property will need to fall at least 45% in value for the investor to be at risk of losing their first penny.

At the other end of the risk scale, junior mortgage loans can offer returns of 15% pa. and LTVs of around 75%. Unless the property’s value increases by more than 15% (of its purchase price) every year, writing a junior mortgage will offer better returns than buying the property directly, and the risks are lower.

What’s the best way to allocate between these asset classes?

Over the years, the fund management industry has developed an intriguing habit. It’s the norm these days for institutional investors to invest a certain amount in each desired asset class and leave it at that. For example, an investor with £10 million to invest in floating-rate assets would do something like allocate £5 million to each of the asset classes described.

But doing this limits your opportunities. Different markets become relatively more or less attractive at different times. Sometimes real estate debt for example is particularly appealing, and other times ABS may be more attractive.

Bringing it all together

Ideally, a strategy that invests in a broad range of credit assets, but manages its exposure relative to floating rates will minimise its exposure to rising interest rates. Flexibility to allocate between those different asset classes at the right time will maximise the investor’s potential returns. Of course, this is easier said than done. Not only do investors need to be well-resourced, with a dedicated team of credit analysts working across public and private debt but they need centres of expertise in each asset class and a fund manager able to identify the relative value between each one at any given time.

If investors have all of this, then the resulting “multi-asset credit” portfolio could offer a stream of benefits. It would have the power to invest in different floating-rate assets and asset classes as and when they become particularly attractive, and hedge the fund’s fixed-rate assets. This will allow investors to mitigate the direct risk that rising interest rates pose and find value in the right assets on a timely basis.

The value of investments can fall as well as rise. This article reflects M&G’s present opinions reflecting current market conditions. They are subject to change without notice and involve a number of assumptions which may not prove valid. The distribution of this article does not constitute an offer or solicitation. It has been written for informational and educational purposes only and should not be considered as investment advice or as a recommendation of any particular security, strategy or investment product. Information given in this document has been obtained from, or based upon, sources believed by us to be reliable and accurate although M&G does not accept liability for the accuracy of the contents.

The services and products provided by M&G Investment Management Limited are available only to investors who come within the category of the Professional Client as defined in the Financial Conduct Authority’s Handbook. They are not available to individual investors, who should not rely on this communication.

M&G Investments is a business name of M&G Investment Management Limited and is used by other companies within the Prudential Group. M&G Investment Management Limited is registered in England and Wales under number 936683 with its registered office at Laurence Pountney Hill, London EC4R 0HH. M&G Investment Management Limited is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority.

More Related Articles...

Published: November 1, 2013

Home »