Emerging markets – the next opportunity

|

Written By: Mike Jennings |

Emerging markets have flattered to deceive in recent times. Mike Jennings of TT International outlines why the tide may have finally turned for investors in the sector

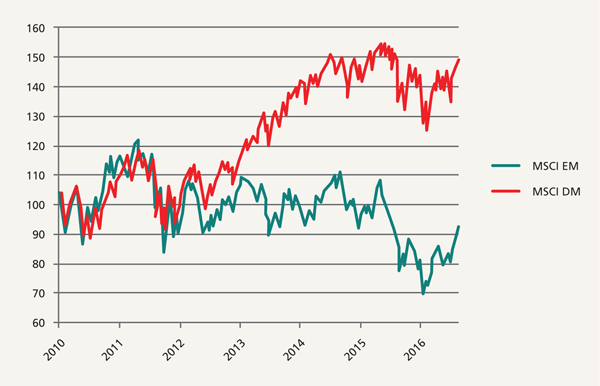

Once the growth darlings of the investment community, emerging market equities have languished for many years. Indeed for the five years to the end of 2015, the MSCI EM index has underperformed developed markets (MSCI World) by almost 50% and, as the chart shows, has generated negative absolute return for investors in the process. But this year all seems to have changed and, at the time of writing, emerging markets (EM) are over 9% ahead. So what has changed and, more importantly, are we entering an era of sustained outperformance?

Figure 1: Index returns in USD terms

Source: Bloomberg

Back in 2007, global investors were scrambling for exposure to emerging markets, China in particular. The economy was growing at a relentless rate in excess of 10% per annum, and the potential was great, with a cheap and seemingly inexhaustible workforce. Indeed such was the appetite for Chinese investments that that year the Shanghai stock exchange more than doubled, and traded just short of 50x earnings. This extreme “irrational exuberance” set the scene for a painful period ahead when foreign investors (including many unsophisticated retail investors) were badly burnt, and the perception of EMs turned from “exciting growth” to “volatile and risky”. In 2008, as the global financial crisis unfolded, Shanghai fell over 60% in USD terms.

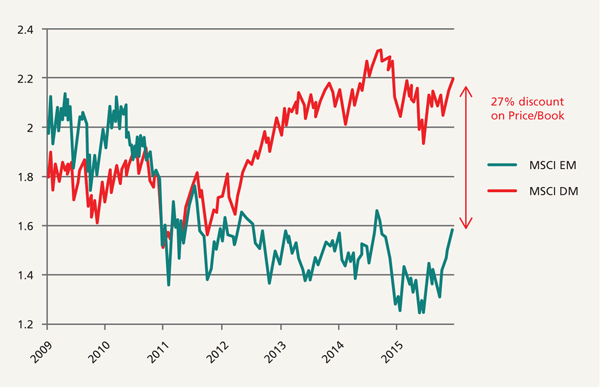

As rates of economic growth slowed in emerging markets – China in particular – many companies were caught out with excess inventory and slowing demand. The fallout from Lehman’s and indeed, closer to home, Northern Rock caused companies and consumer alike to tighten their belts, thus compounding the slowdown for Chinese exporters. As Figure 2 shows, this process gradually caused investors to be willing to change from paying a premium valuation for EMs to requiring a substantial discount. On valuation metrics of Price/Earnings and Price/Book (shown), emerging markets have been systematically de-rated relative to their developed market cousins over the ensuing years.

Figure 2: Price/Book value

Source: Bloomberg

But in late 2014 and into 2015, many issues came to a head to flush out the last remaining bears. The collapse in the oil price – commencing most substantially in Q4 2014 – caused a spike in risk aversion and therefore a stampede of foreign investors fleeing EMs. Paradoxically, with many EM countries being net oil importers most particularly in Asia, this was a helpful catalyst for many economies whose fiscal and trade deficits have materially improved since. Unfortunately however, weak commodity prices compounded the substantial problems already evident in Russia, Brazil and South Africa in particular. Russia was also constrained by sanctions commencing in late 2014, Brazil has been reeling from the Petrobras scandal and impending impeachment of President Rousseff, whilst South Africa has been on a downward economic spiral through years of political turmoil and economic mismanagement.

With – in most cases – highly immature domestic savings bases (with little pension fund saving for example), emerging stock markets and their currencies often suffer disproportionately due to their dependence upon foreign capital flows. It is often the currencies, therefore, which bear the brunt of the sharp downdraught when foreigners run for the exit. In calendar 2015, for example the Brazilian Real fell by 33% against the US Dollar. The Russian rouble did the lions share of its collapse in the fourth quarter of 2014, with a 32% fall in those 3 months alone; and the South African rand, whilst depreciating for many years, fell 25% against the dollar in 2015. And these were not the exceptions. Even the larger emerging markets of India and Indonesia suffered sharp currency weakness as investors shunned them for the safety of their home markets.

Figure 3: Indonesia, Brazil and India FX basket (equally weighted) versus USD

Source: Bloomberg

This currency weakness was the last straw for swathes of emerging market investors. Many institutional investors threw the towel in on emerging markets altogether while others grimly held on in the comfort that at least they were underweight their benchmark. Such a position became as consensual as those who were bulls of China back in 2007 – a dangerous position to be in.

Fundamentally things have begun to change in favour of emerging markets. The latest IMF economic projections were notable in that their forecast for emerging market growth remained unchanged, whereas those in most developed markets were cut in the aftermath of the Brexit vote. Similarly, whilst the IMF have developed economic growth only modestly accelerating in 2017, EM growth is expected to surge ahead to an impressive real GDP growth rate of 4.6%. Indeed, helped by the currency weakness of recent years, we are beginning to see positives at the company level with signs of accelerating earnings expectations ahead.

Globally, there is an excellent inverse correlation over time between EM relative performance and the dollar (a weak US dollar is helpful for EM and vice-versa). The risk aversion trade, and the relatively solid economic position of the US has caused a multi-year dollar surge, and thus a severe headwind for EM asset prices. This would appear to have come to an end as the Fed has persistently put off rate rises throughout this year so far. The UK’s vote to leave the European Union has, perhaps counterintuitively, also helped the relative attractions of emerging markets. Whilst political uncertainty has historically been largely an EM phenomenon, the Brexit vote, coupled with the approaching Italian referendum, US election and German and French elections next year have placed the focus in this regard more on the developed world. With the vote clearly having had an impact on the Fed’s decision to defer its next rate rise, it allowed many other countries – both in the DM and EM worlds – to ease theirs further, and in doing so loosened conditions, helping liquidity and therefore creating a positive backdrop for emerging markets.

For global asset allocators, we live in challenging times. Conventional metrics suggest that bond markets are in totally uncharted territory, with over $13 trillion of bonds in issue trading at a negative yield to maturity. Equities, whilst certainly not so extreme, would also appear to be expensive on most historic metrics. Though in the hunt for yield, equities offer substantially superior returns than are available in most bond markets. Quantitative easing has certainly created the conditions for asset bubbles to thrive and as such, has also created an artificial and challenging environment in which to invest.

Emerging markets offer respite from this. With bond yields heading ever closer to zero (or below), emerging debt looks comparatively attractive. For Japanese investors, a 4.3% yield in a Brazilian 10-year government bond might look appealing relative to costing 0.8% per annum at home; or a 7.1% yield in India might look very attractive relative to just 0.55% now available in UK government debt. Indeed EPFR report that EM bonds saw a $20 billion in-flow over the past seven weeks alone, with bond fund allocations to EM now at a four year high. As their own yields fall, so bond gains fuel their equity cousins. For EM equities, this is particularly powerful as so many investors scramble to re-buy. Emerging market equity funds saw a $5.1 billion inflow from investors for the week ending August 17th – the most in 58 weeks – but in comparison to the multiple years of outflows, investors have plenty more scope to accumulate positions. And with emerging markets largely missing out on the five year re-rating of western markets, investors can pay multiples which look historically attractive. Paying 13.5x times this years earnings to buy a basket of emerging market stocks would appear to be rather more palatable than paying 18.6x for the US equivalent, for example.

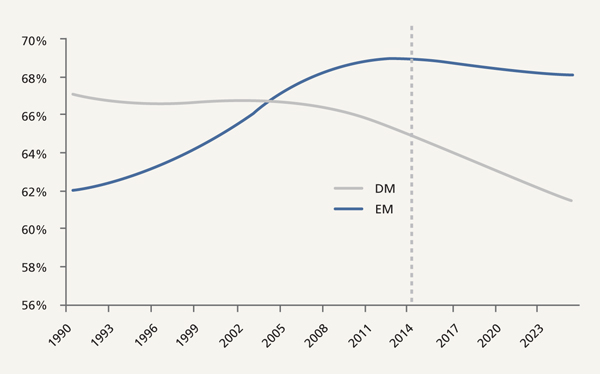

For longer term investors, one major headwind that we are beginning to feel the effect of is the problem of an ageing population. Emerging economies are not immune from this demographic time bomb but, as Figure 4 shows, the collapse in working age population is far more severe in the developed world. If one delves a little deeper, we find that the emerging markets vary considerably on this metric. Indeed the growth of over 65s in China, Brazil and Korea combined is twice the rate of the developed world. So selectivity is key, and at the other end of the spectrum selected emerging countries have a growing advantage from a young and dynamic population. In Pakistan the median age of the population is 22.6 (versus 40 in the UK, and 46.5 in Japan), with India at 27.3 and the Philippines at 23.2, for example. Thus, active management in the asset class is particularly attractive going forward.

Figure 4: Working age population (aged 15-64)

Source: UN census 2015

Investors in emerging markets can never be complacent. In a large and geographically diverse group of countries, it is rarely a smooth ride. In aggregate however, the asset class had become a pariah, and valuations had collapsed as a result. Selectivity is always key in emerging markets, so active management should always have the potential to add substantial value against the index. With the hunt for scarce income pointing investors towards EMs, and indeed the hunt for equally scarce growth doing the same, we expect a multi-year tailwind ahead for emerging market investors.

More Related Content...

|

|

|