Infrastructure investing in a post-Covid world

|

Written By: Ingrid Edmund |

|

Benjamin Kelly |

Ingrid Edmund and Benjamin Kelly of Columbia Threadneedle Investments look at how the Covid-19 pandemic has highlighted the importance of sustainability in infrastructure investment

The nature of sustainable infrastructure investment has been changed by Covid-19. The economic impact of the pandemic, as governments around the world restrict movement and business activity in an attempt to slow the spread of the coronavirus, has prompted unprecedented levels of state spending in areas of infrastructure ranging from healthcare and education to employment programmes.

In response, capital markets have seen a record level of issuance of social bonds to raise funds for such projects. Morningstar estimates that European sustainable funds have reached more than $1 trillion of assets for the first time – with the third quarter alone seeing more than €50 billion¹.

Heading into the pandemic, sustainable investment was typically more likely to focus on the environment and climate change mitigation strategies. But investing to produce more beneficial or equitable social outcomes is now firmly in the spotlight. This is unlikely to fade as the world emerges from the pandemic. There is growing realisation by investors that infrastructure investments have long-term consequences on communities, and ultimately, integrating ESG is not just a risk mitigation tool but a return generator and an opportunity to create further value by shaping positive outcomes.

Climate change investment and Covid-19

The idea that investing in infrastructure can benefit the environment and/or mitigate the impact of climate change is not new. What is different is the pandemic has changed some of the dynamics.

Reduced travel, industrial activity and electricity generation during Covid-19 saw global emissions fall by up to 7% in 2020, according to the UN Environment Programme.² This impact will likely extend well into 2021. Further lockdowns have already been imposed across the world, and it may take several years for demand in sectors such as air travel to return to pre-pandemic levels. Despite this, atmospheric CO2 is continuing to rise. This shows that while the measures imposed during the pandemic are helpful in terms of reducing global emissions, they remain far from what scientists estimate is needed.

Meanwhile, the downturn in business activity in 2020 has also led to a sharp fall in fossil fuel prices, and as economies return to growth there is the chance that expansion could be underpinned by cheaper oil and gas, with a concomitant increase in emissions. Furthermore, while the share of renewable energy production has been increasing exponentially it only translated into 18% of the EU’s gross final consumption in 2018, with results in transport and heating/cooling particularly below expectations. This highlights that more needs to be done to prevent economic recovery leading to a rebound in emissions.

The post-pandemic period is likely to provide opportunities to increase investment linked to climate-change mitigation: the EU, for example, has indicated it will put the environment at the centre of its Covid-19 economic recovery plans³, while the UK has recently announced more ambitious proposals to meet its emissions targets⁴. The green stimulus doesn’t only achieve a reduction in emissions but also fosters investment which can boost job creation in manufacturing, construction and small and medium-sized businesses, and save consumers money.

In the US, president-elect Joe Biden has said the US will rejoin the Paris Agreement⁵, and several US states already have goals in place to hit at least 50% renewable energy by the end of the decade⁶.

There are no signs that the tough climate targets put in place by governments around the world prior to the Covid-19 crisis will be watered down, which bodes well for the future of sustainable investment. An example is the endorsement of green hydrogen by governments. Hydrogen has been positioned as the clean technology solution to decarbonise areas of the economy such as transportation, which has until now proved challenging with electrification. Europe’s €180 billion investment to scale up and deploy clean hydrogen⁷ could see a sharp reduction in costs and promote the scaling up of production and use of renewable hydrogen.

This will provide additional opportunity in creating a smarter, reinforced distribution grid and new balancing solutions that will enable the integration of more decentralised renewables resources.

A boom in social bond issuance

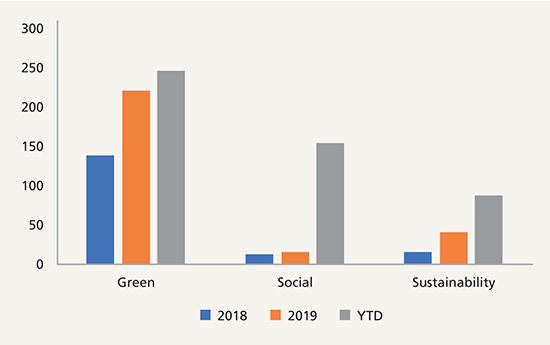

As a barometer for identifying trends within environmental and social investing, look no further than the issuance of specific use of proceeds bonds, specifically green, social and sustainability. Issuance in 2020 was underpinned by a sharp increase in the issuance of social bonds (more than 700% year-on-year⁸) – where debt financing is channelled to specific projects with agreed socially beneficial outcomes. This could be the creation of jobs, setting up healthcare programmes or facilities, or the provision of education or training. The pandemic has had a devastating impact in all of these area.

At the end of November a total of $155 billion were issued⁹, an increase of 869% on the same period in the previous year. Around $100 billion was raised by issuing dedicated Covid-19 bonds covering either social and/or sustainability projects¹⁰. But a record year for social issuance has not been at the expense of green. And this whole segment of issuance, i.e. green, social and sustainability, was on the cusp of issuing $0.5 trillion in debt in 2020 – another record.

Figure 1: Social, green and sustainability bond issuance, 2018-2020 ($billion)

Source: Bloomberg/World Bank. YTD figure is to 30 November 2020

Viewing sustainability investment through a new lens

The wide range of social bonds issued, and the likelihood of this trend continuing for the foreseeable future, means investors and institutions now have a much wider choice of socially beneficial investments – alongside those with green and/or sustainability credentials.

An example of how social and environmental outcomes can be incorporated into a strategy is the Columbia Threadneedle European Sustainable Infrastructure Strategy, which earlier this year invested in Lefdal, a data centre based in Norway. Lefdal has excellent environmental credentials, in particular its industry-leading levels of energy efficiency, which are based in part on its use of water from a nearby fjord for cooling¹¹.

But Lefdal also has a significant social impact: the role it plays in supporting Norway’s digital infrastructure is vital in terms of providing connectivity to previously underserved communities. This can improve access to digital training and help create new employment opportunities.

The European Sustainable Infrastructure Strategy also recently acquired Condor Ferries, the primary facilitator of freight and passengers between the Channel Islands, the UK and France. While shipping often attracts questions in terms of its suitability within sustainable investment portfolios due to carbon emissions, businesses such as Condor play a vital social role in providing freight and physical connectivity services for remote or island communities. In turn, these services can support healthcare, food security and employment opportunities. Certainly as vaccines supporting Covid-19 are distributed across the world, freight services will be a critical enabler of delivery.

But this doesn’t mean the environmental impact can, or is, being ignored. In the case of Condor, the strategy is working to improve the environmental profile of the business’s fleet as well as its onshore activities. This will involve reducing waste and improving efficiency, while making a transition to cleaner propulsion technologies.

Social infrastructure investment after the pandemic

The socioeconomic impact of the coronavirus is likely to be long-lasting: it already appears to have exacerbated income inequalities in many communities, with employment among better paid white-collar workers less likely to have been affected than those in customer-facing roles or jobs that cannot easily be done remotely.

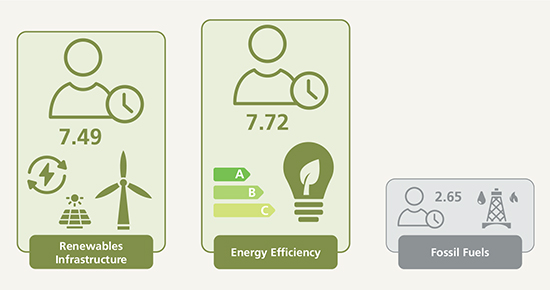

But the rise in social investing may have helped create a better understanding of the interplay between environmental and social concerns. For example, the EU sees a new green deal as the route out of the pandemic-induced recession because of its ability to create thousands of jobs, not just because it will help the bloc reach its emissions deadlines. Recent research suggests investment in green projects could create up to three times as many jobs as investment in competing fossil fuel-based projects (Figure 2).

Figure 1: Jobs per million investing in green projects vs. fossil fuels

Source: Will Covid-19 fiscal recovery packages accelerate or retard progress on climate change? May 2020 Cameron Hepburn, Brian O’Callaghan, Nicholas Stern, Joseph

A reduction in reliance on oil and gas can have additional social benefits: improvements in air quality as a result of the switch to electric motor vehicles, for example, are expected to deliver major health benefits, and these will be felt disproportionately by those living in more crowded urban areas.

Ultimately, progress in minimising the impact of climate change will inevitably have huge social implications in terms of reducing the prevalence of extreme weather events, thereby limiting the extent to which they can ruin harvests, damage property and displace people in the decades ahead.

Important information

* Reference to the Fund are for information purposes only.

For use by Professional and/or Qualified Investors only (not to be used with or passed on to retail clients). This is an advertising document.

Past performance is not a guide to future performance. The value of investments and any income is not guaranteed and can go down as well as up and may be affected by exchange rate fluctuations. This means that an investor may not get back the amount invested. Your capital is at Risk.

The analysis included in this document has been produced by Columbia Threadneedle Investments for its own investment management activities, may have been acted upon prior to publication and is made available here incidentally. Any opinions expressed are made as at the date of publication but are subject to change without notice and should not be seen as investment advice. Information obtained from external sources is believed to be reliable, but its accuracy or completeness cannot be guaranteed.

The mention of any specific shares or bonds should not be taken as a recommendation to deal. This presentation is not investment, legal, tax, or accounting advice. Investors should consult with their own professional advisors for advice on any investment, legal, tax, or accounting issues relating an investment with Columbia Threadneedle Investments.

These materials may only be used in one-on-one presentations. This document is distributed by Columbia Threadneedle Investments (ME) Limited, which is regulated by the Dubai Financial Services Authority (DFSA). The information in this document is not intended as financial advice and is only intended for persons with appropriate investment knowledge and who meet the regulatory criteria to be classified as a Professional Client or Market Counterparties and no other Person should act upon it.

Threadneedle Asset Management Limited (TAML), registered in England and Wales, No. 573204. Registered Office: Cannon Place, 78 Cannon Street, London EC4N 6AG, United Kingdom. Authorised and regulated in the UK by the Financial Conduct Authority. TAML has a cross-border licence from the Korean Financial Services Commission for Discretionary Investment Management Business.

Columbia Threadneedle Investments is the global brand name of the Columbia and Threadneedle group of companies.

1. Prequin Pro, October 2020

2. https://www.unenvironment.org/emissions-gap-report-2020 9 December 2020

3. https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/recovery-plan-europe_en

4. https://www.ft.com/content/3eda6c6f-265f-4804-a017-a260d1e101cc

5. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2020/nov/08/joe-biden-paris-climate-goals-0-1c

6. Bank of America Merrill Lynch, May 2020.

7. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/QANDA_20_1257

8. Columbia Threadneedle analysis, 2020

9. Bloomberg, November 2020

10. Columbia Threadneedle Investments, June 2020.

11. Lefdal Mine Data Center, https://www.lefdalmine.com/cooling/#:~:text=European%20leading%20Cooling%20solution%20Lefdal%20Mine%20Datacenter%20is,used%20for%20cooling%20with%20a%205%20KW%2Frack%20configuration

More Related Content...

|

|

|